6 days in Perth, Australia- 5/22- 5/27/2024

Day 5-Wave Rock Day tour-5/26/2024

York

Today’s 13.5-hour journey from Perth to Wave Rock unfolded in a gentle rhythm,

each stop adding a layer to the experience.

Our first break was York, a quiet heritage town where historic buildings and

tree-lined streets offered a calm, early-morning pause. From there, the road

opened into wide Wheatbelt country as the bus carried us toward the ancient

Mulka’s Cave. A short stop followed at the Wave Rock Wildlife Park, a quick

but fun detour, and then, finally, the landscape shifted again as we reached

the highlight of the journey,

Wave Rock, rising like a frozen surge of stone in the middle of the outback.

The

historical York is the first town founded in the Avon Valley. York is one

of Western Australia’s most picturesque towns with charming architecture. This

town was the first inland European settlement in Western Australia, founded

back in 1831. We took a stroll along the main town strip and saw

many of the old buildings which are still in use today.

During the late 1800s, the gold rush brought wealth to the

region. York prospered because it was a kind of gateway town, lots of

goldfield prospectors passed through or used its services. Many of York’s

heritage buildings are preserved because of that boom era, and the town today

leans heavily into its history as a tourism draw.

York Motor Museum sits in a building that has evolved over time: originally,

in the 1800s, this was a cottage + bakery site. By about 1907–1912, the

building was rebuilt (or significantly altered) and eventually used as a metal

workshop. During WWII, part of it was used by the army, and later Peter Briggs

turned it into the York Motor Museum, housing a large collection of vintage,

classic, and racing cars. The museum is a real highlight, it connects the

town’s heritage with Australia’s motoring history.

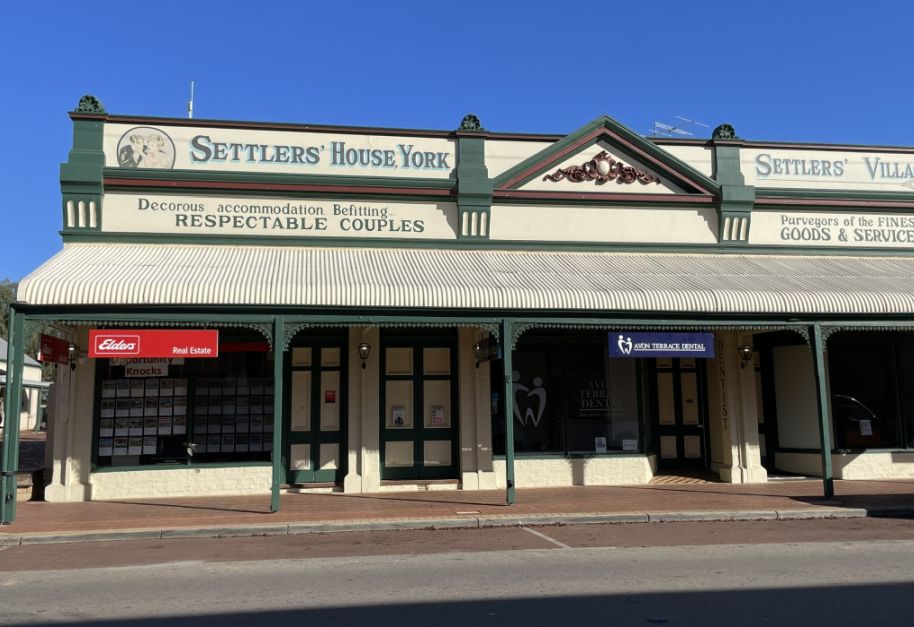

The central building is a collection of single-story

commercial shops built in stages over time, primarily between 1892 and 1907.

The building is association with the

early commercial activities that drove the boom period of York's history.

It is considered a good,

intact example of a commercial premises in the Victorian Regency architectural

style. In the 1970s, it housed businesses like a hardware store, the York Four

Square Store, and a Retravision electrical store. These buildings are part of

the larger York Town Centre Precinct, which is recognized for its historical

environment that helps in understanding the development of York as the first

inland town in Western Australia.

We stumble on the only Vietnamese coffee shop in York.

York Post Office on 134 Avon Terrace was constructed in 1893, designed

by George Temple-Poole, a prominent government architect. It’s built in a

Federation Arts & Crafts (sometimes called Federation Free Style) design, so

you’ll see more playful lines and decorative brickwork. This building is

particularly important historically: it’s the oldest surviving two-story

post-and-telegraph building in Western Australia. It wasn’t just a post

office, it also included living quarters for the postmaster. Its role was

critical during the gold rush; York was an important stop, and the

post/telegraph office reflected the town’s growing role.

|

|

The Western Australian Bank on 147 Avon Terrace is an impressive two-story

building built in 1889, designed by the noted architect Talbot Hobbs in a

Victorian Academic Classical style. Architecturally, the building's

classical façade, columns, and decorative cornice make it a standout on Avon

Terrace. It originally housed not just the banking operations but also

the bank manager’s residence upstairs, a common Victorian-era bank design.

This bank building is one of the oldest in WA. Later, the Western Australian

Bank merged with the Bank of New South Wales (1927), which eventually became

Westpac. In recent years, the local Westpac branch here closed (2019), marking

the end of a long banking era for York.

York Fire Station on 151 Avon Terrace was originally built in 1897, but not as

a fire station, it was first used as council chambers for the York Municipal

Council. Designed by Christian Mouritzen, the building is in a Federation Free

Classical style (with Romanesque and Mannerist touches), you’ll notice red

brick and classical lines. After the Town Hall was built, the council moved

out, and this building was repurposed into the fire station. Nowadays,

it's not a fire station anymore: the building has been converted into a

bookshop.

We stopped by at coffee shop on the main street.

We sat outside and had a meat pie, sweet cinnamon brioche, and coffee.

This corner building is the Imperial Hotel (sometimes called the Imperial

Homestead Hotel), is a big two-story hotel on Avon Terrace with the double

verandahs/metal balconies and the little pointed roof pediment at the corner.

It was built in 1886 in a Victorian-filigree style and has been a prominent

Avon Terrace landmark ever since.

The entrance of the Imperial Hotel on Avon Terrace.

Avon Terrace.

York Courthouse Complex (Court House, Police Station & Gaol). his

complex spans a long period: first structures (cell block and police quarters)

date back to 1852, with later additions through to 1896. The design was done

by George Temple-Poole, again, he was very active in public architecture in

WA. The complex include a gaol (jail)/cell block for convict laborer and

other, a courthouse, a Police quarters, stables, a troopers’ cottage, and an

exercise yard. Today, the complex has been repurposed as a museum and

art gallery under the National Trust.

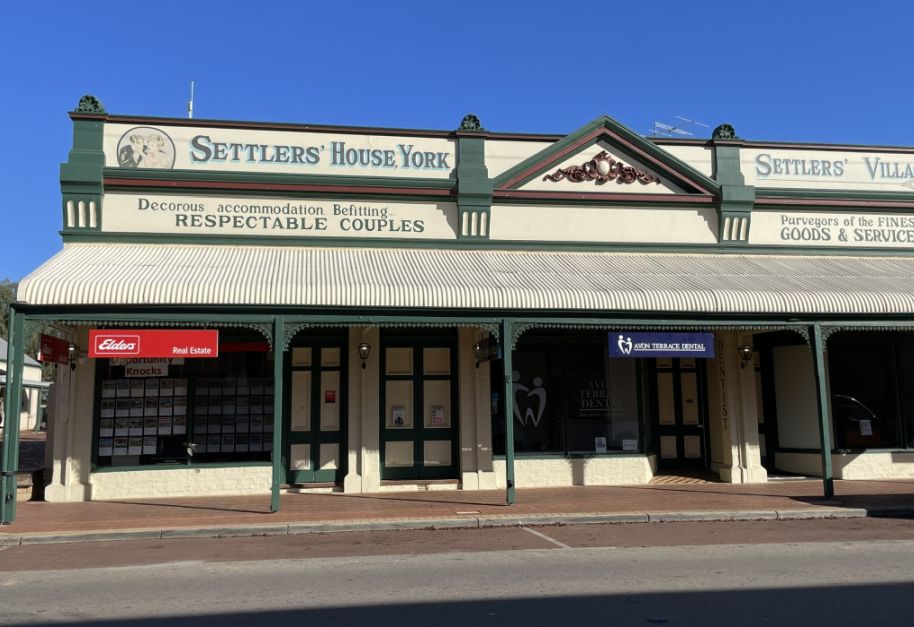

The settler's house is a really charming spot.

It is now a pub/accommodation called Settlers House York. Part of the

building goes way back , the “tavern” section is from around 1845, which means

it's one of the older remaining buildings in town. today, it operates as

a heritage-style hotel with a mix of modern and old rooms, plus a

restaurant/tavern, making it a cozy base to absorb York’s history.

We are on Avon Terrace, the main street in York, and we are headed to York

Town hall (the building at the end).

York Town Hall on Avon Terrace was built in 1911 and is one of York’s most

flamboyant civic buildings. Architecturally, it mixes styles: some call it

Federation Free Classical, others note Victorian Mannerist influences with

soaring columns, decorative pediments, and a large semi-circular window above

the main entrance.

When it was built, it was said to be the largest

public hall in Western Australia. Today, it houses the York Visitor Center, so

it's not just a historic shell, it's a living part of the town.

We hopped on the bus to our next destination.

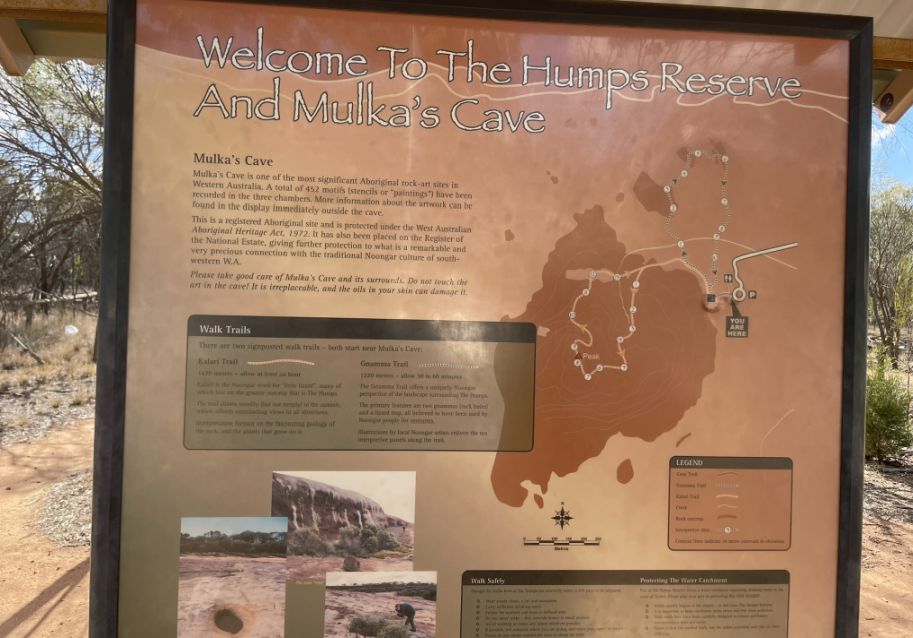

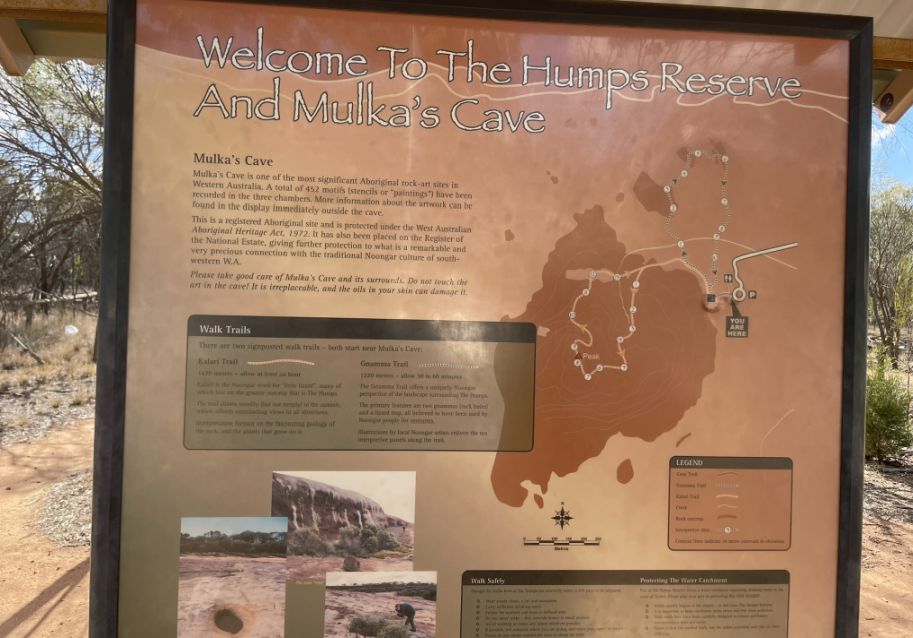

Mulka's cave

As the bus leaves York behind, the scenery quickly shifts into the deep

Wheatbelt, which is is the largest agricultural

producer in Western

Australia, surrounding the Perth metropolitan area and extending north and

east. The economy is dominated by

agriculture, which is the source of nearly two-thirds of the state's wheat

production, about half of its wool production,

and the majority of its lamb and mutton, oranges, and honey.

The road grows long and quiet, stretching straight ahead with hardly

another vehicle in sight. On both sides, the landscape turns dry and

sun-bleached.

a

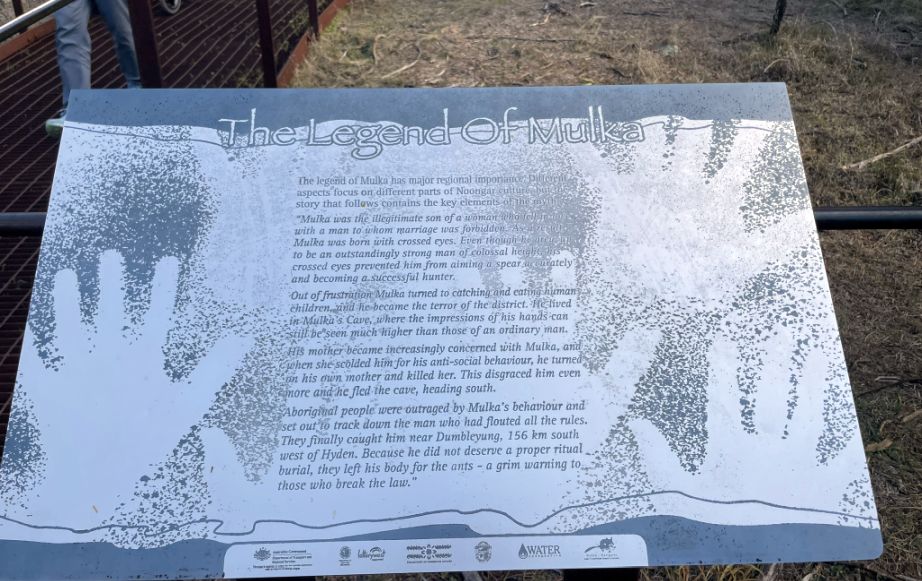

According to Noongar tradition, the cave is named after Mulka, the son

of a woman who broke a sacred law by having a forbidden relationship. Because

of this, Mulka was born with a deformity: his eyes were set so low on his face

that he could not look forward, only downward. Even as a child, he grew

unnaturally tall and powerful. Mulka was raised with love, but he struggled to

fit into the laws and values of his people. As he grew older, he became

unpredictable, restless, and finally violent. He began to attack travellers,

then eventually turned to harming children in nearby camps. When his mother

confronted him, Mulka reacted in rage and killed her. After the murder, Mulka

fled into the bush, living in the granite landscape around what is now Hyden.

The people of the region banded together and pursued him. Eventually, they

caught him and punished him for breaking their most sacred laws. Mulka’s Cave

is said to be one of the places he used as a shelter. The handprints on the

cave ceiling are part of this story, they are believed to be the prints of

people who once lived here, watching over the cave and preserving its memory.

The tale is a reminder of the Noongar belief in responsibility, law, and

balance. It’s both a legend and a moral story, carried across generations.

When we arrived at Mulka’s Cave, the first thing you notice is the air is dry.

This area receives very

little rainfall, with long hot summers and short, erratic winters.

The landscape around Mulka’s Cave sits in the Wheatbelt, one of the oldest and

driest landscapes in Western Australia. The vegetation here has a very long

history shaped by three main forces: ancient soils, long-term drought cycles,

and human land-clearing.

a

During these dry cycles, Mallee eucalypts naturally shed branches to conserve

energy. So the dead branches you’re seeing are part of their survival

strategy, the tree drops what it can’t afford to keep alive.

The soils here are some of the oldest in the world, millions of years old and

extremely low in nutrients. Only hardy plants can survive, which is why you

see lots of mallee-type eucalypts, scrubby shrubs, and saltbush and heath

vegetation.

These plants evolved to survive on almost nothing, storing water in their

roots and dropping leaves or branches during hard seasons.

The Red Ironbark, scientifically known as Eucalyptus

sideroxylon is a striking,

medium-to-large evergreen tree native to eastern Australia.

It is highly valued for its

distinctive bark, beautiful flowers, and extremely durable timber.

The Red Ironbark's wood is one of the hardest and densest timbers in the

world, so dense that it reportedly will not float in water.

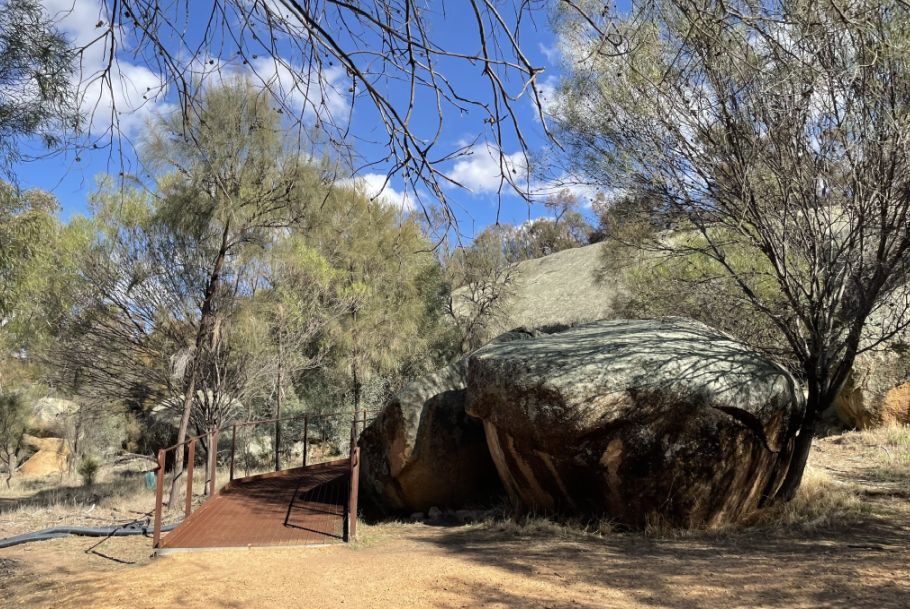

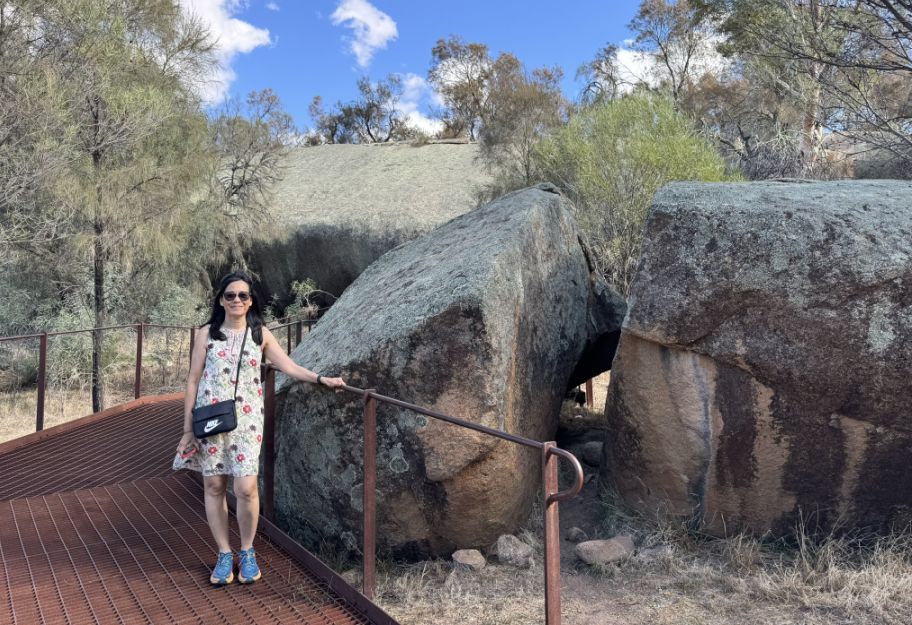

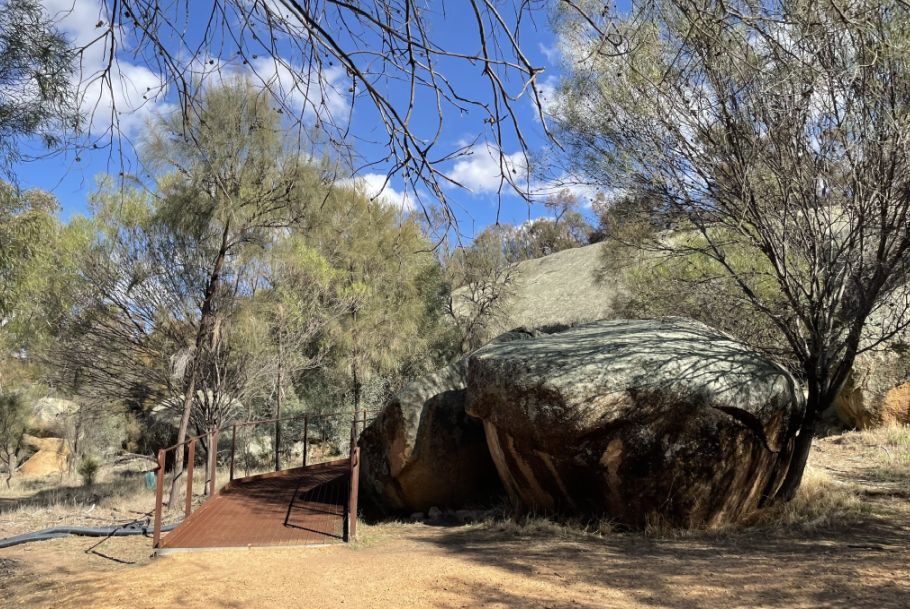

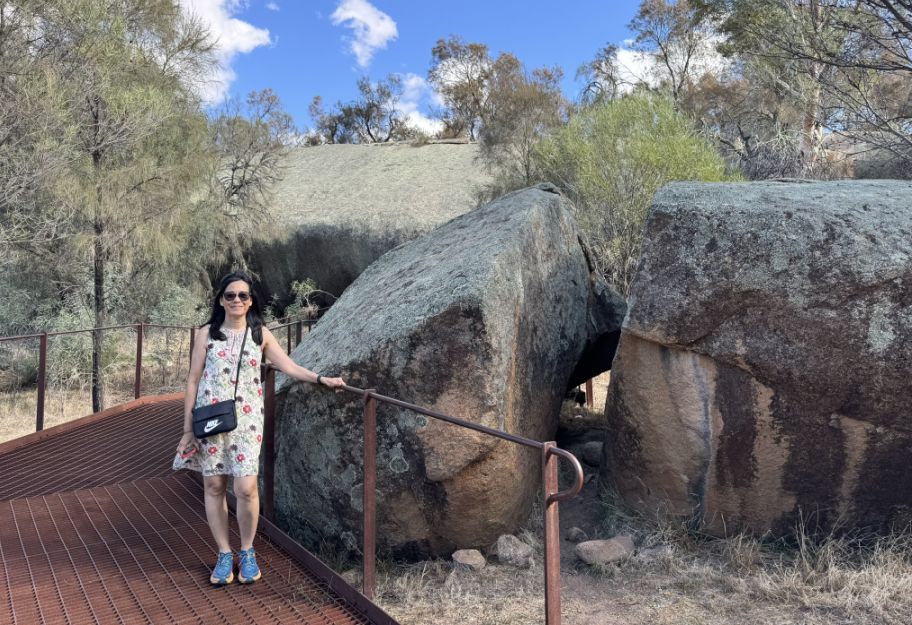

The path leading toward the cave is short and gentle, winding through clusters

of granite boulders. As you get closer, the massive rock formations rise

ahead, rounded, worn smooth by thousands of years of wind and weather.

The entrance to the cave looks low and shadowed, almost hidden under an

overhanging granite shelf.

Inside Mulka’s Cave, the space feels cool and still,

and the granite walls curve around you like a natural shelter. From where

we are standing, we can see that the cave isn’t very deep, but the shapes of

the rocks make it feel like a small maze carved into the stone.

Toward the back, that small opening looks almost like a low doorway cut into

the rock. It lets in some light, just enough to outline the shadows inside.

The opening feels mysterious, like an escape route, a lookout point, or a

hidden corner used long ago.

Scattered around the floor are large, rounded boulders, some leaning into the

walls, others sitting like natural seats. They’ve been smoothed over time by

weather and footsteps, giving the cave those familiar, curved granite shapes

that are common in this landscape.

Panoramic view of the cave from the inside

Then, as your eyes adjust, you begin to see the handprints and markings left

by the Noongar people.

They appear faint but unmistakable, ghostly outlines in red ochre, spread

across the stone like a silent gallery of presence. Some prints are small,

some larger, each one layered with stories and meaning that have endured for

generations.

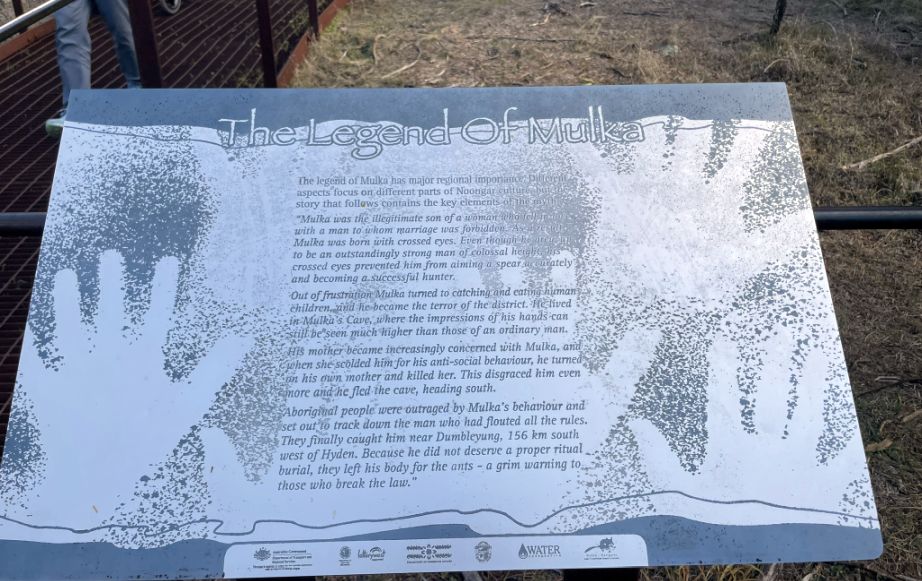

A panel telling the Legend of the Cave.

We are now leaving the cave.

You can really see how low the opening of the cave is.

Lots of dead trees on the property.

This area is definitely super dry.

The Lemon-scented Gum while a beautiful and aromatic Australian native, is

actually not native to the area around Mulka's Cave (Hyden) or the

York/Avon Valley region of Western Australia. The

key here is that the Lemon-scented Gum is very adaptable and drought-tolerant

once established, which is

why it has been widely planted outside its native range throughout Australia,

including in the dry WA Wheatbelt.

a

Known to be a drought-resistant

tree that thrives in full sun and well-drained soil.

This makes it an excellent choice for landscaping in dry climates like

Hyden's, where water conservation is essential.

Like many trees, it

requires regular

watering during its first year

to establish a strong, deep root system.

Once established, it requires little to no additional summer watering.

Heading to the bus.

Wave Rock Wildlife Park

We are now at the Wave Rock Wildlife Park. The park is

set on about 7 acres of natural bushland and houses a mix of native Australian

animals and some exotic species.

This is black swan s the most powerful and pervasive

symbol of Western Australia (WA). It is the official Bird Emblem and

appears prominently on the State Flag and the Coat of Arms of Western

Australia.

An Albino Kangaroo laying around the park. The white coloring is a

result of a genetic condition called leucism (a partial loss of pigmentation)

or albinism (complete lack of pigment). Seeing a white kangaroo in nature is

extremely rare, making it a powerful symbol of uniqueness or the unexpected

Australian experience.

The Wave Rock Wildlife Park is known for having a population of these rare

white kangaroos, showcasing a unique variant of Australia's national animal.

NEXT... Wave Rock