6 days in Perth, Australia- 5/22- 5/27/2024

Day 5-Wave Rock/Hyden Rock-5/26/2024

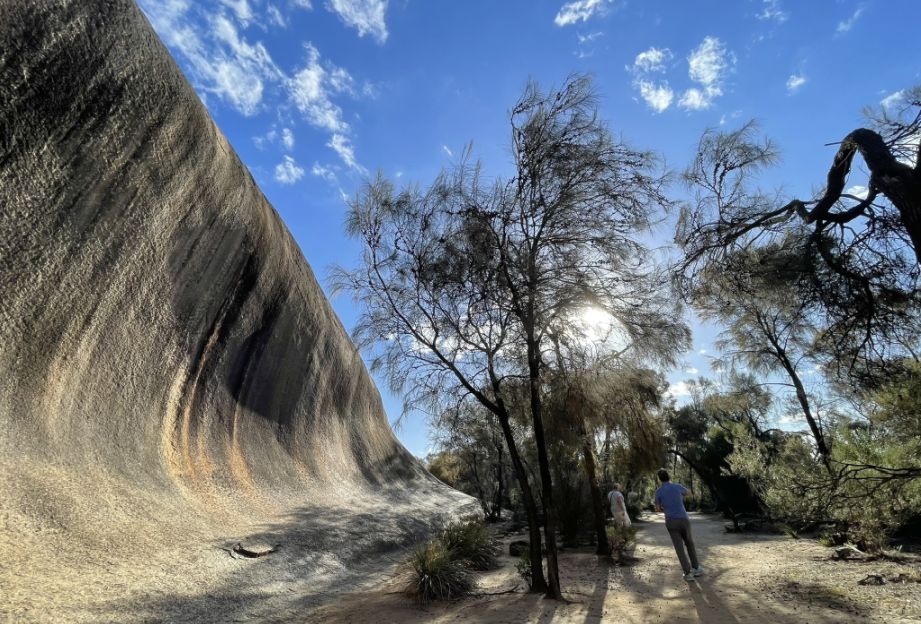

Wave Rock sits on the northern side of Hyden Rock, a massive granite dome that rises suddenly from the flat wheatbelt landscape. Hyden Rock itself is more than two billion years old, and Wave Rock is one of its most striking features, a long, curling cliff face that looks like a frozen ocean wave. The dramatic shape formed over millions of years as rainwater flowed down the granite, slowly eroding the lower section faster than the upper section. Minerals carried by the water stained the rock in dark bands, creating the rippled, wave-like colors we see today. Together, Hyden Rock and Wave Rock tell the story of deep geological time, natural sculpting forces, and the unique landscapes of Western Australia.

For millions of years, water flowed down the face of the rock. Minerals in the water stained the granite, creating the dark vertical stripes. The lower part of the granite face eroded faster than the top, and this undercutting produced the dramatic curling shape that looks like a frozen ocean wave.

|

|

|

The wave itself is about 50 ft. high and roughly 360 ft. long.

Indigenous Noongar people have known and told stories about the rock for thousands of years. Wave Rock and nearby sites like Mulka’s Cave feature prominently in Dreaming stories connected to creation spirits, water, and ancestral beings.

That's me at the end, trying to do a curve wave with my arms. The vivid vertical streaks of color are one of the most remarkable features: Blacks and Greys: These colors are usually manganese oxides, which were also carried down and deposited by the runoff water. These mineral stains are what give Wave Rock its characteristic striated, or striped, appearance, like a giant, color-washed cliff face.

Standing at the base of Wave Rock feels almost surreal. The cliff towers above in a perfect arc, its colors shifting from gold to charcoal, its surface smooth and immense. The scale is so large and so unexpected in the middle of the outback that it feels like stepping into a natural amphitheater shaped by time itself. It’s one of those places where you can’t help but pause, look up, and feel the quiet power of the landscape.

We are now walking toward the far end of Wave Rock, where the trail rises gently and leads up to the top of Hyden Rock.

It is really amazing to see the wave rock, and standing below it.

This is the far end of the wave rock.

At the end of Wave Rock, a set of stairs begins to climb upward, leading the way to the top of Hyden Rock.

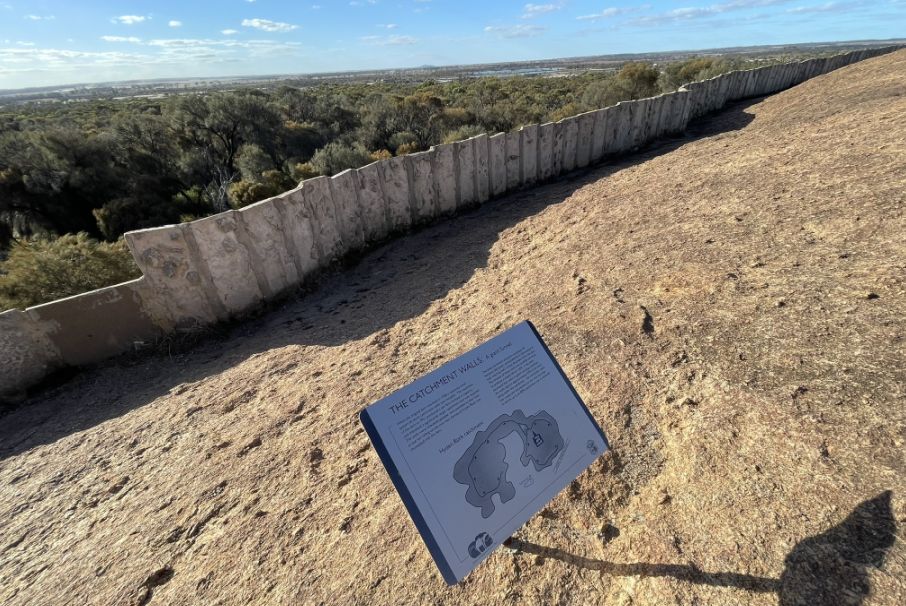

As soon as you climb to the top of Hyden Rock, the landscape suddenly opens up. Hyden is a very dry region, and water was historically scarce, so early settlers realized that the huge granite dome could act as a natural watershed.

They constructed a stone catchment wall, to direct runoff, Steel/Concrete channels to funnel the water, and a storage reservoir which is the small lake on the left. This system collected thousands of liters of clean rainwater and supplied the town before modern pipelines were built.

Today, the reservoir isn’t essential for day-to-day drinking water, but the

historic catchment system remains as a reminder of how remote communities

engineered solutions using the natural landscape.

We are now on top of the granite boulder, and from here you get a panoramic view of the wheatbell and salt lakes.

The low stone wall you saw curving around part of the summit was built in the 1950s and 1960s. Its job was to guide rainwater that naturally runs off the granite into a controlled channel.

Closer view of the catchment walls.

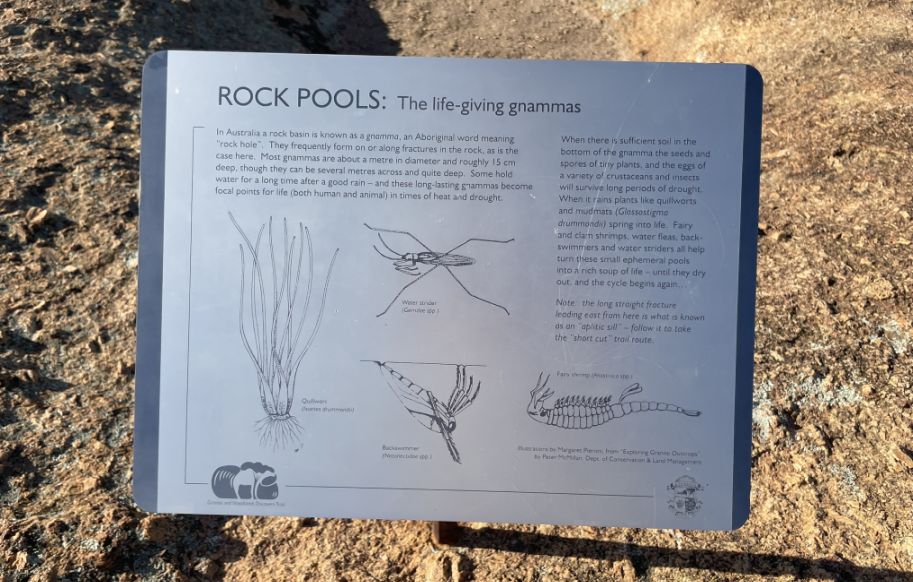

As we reached the top of the granite dome, there are shallow, rounded

depressions scattered across the surface. These are called rock pools or

gnammas. Over thousands to millions of years, small pockets in the granite

collected water. Windblown sand and plant debris settled inside. The trapped

water and gritty sediment slowly wore the granite down. Over time, each small

depression grew deeper and wider, forming a natural “pool.” For the Noongar

people, rock pools were extremely important.

They served as freshwater sources in a dry landscape, helping sustain people,

animals, and plant life. Many of these gnammas were carefully protected and

maintained.

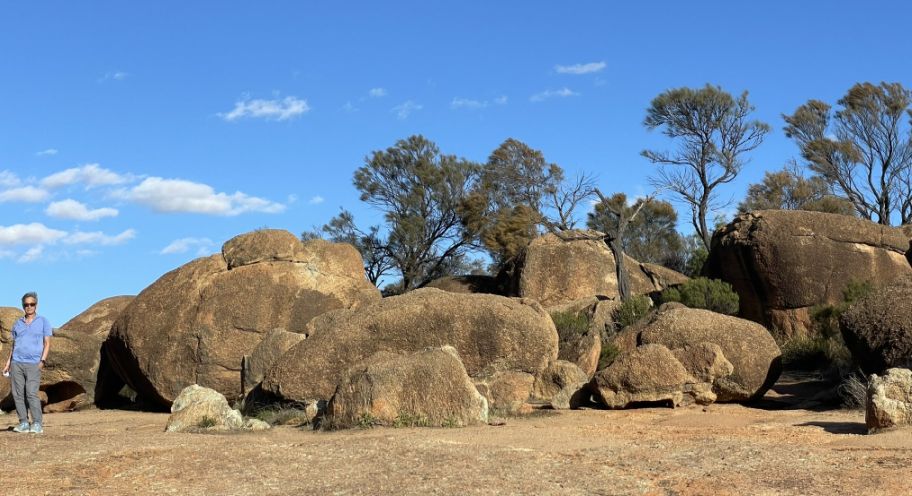

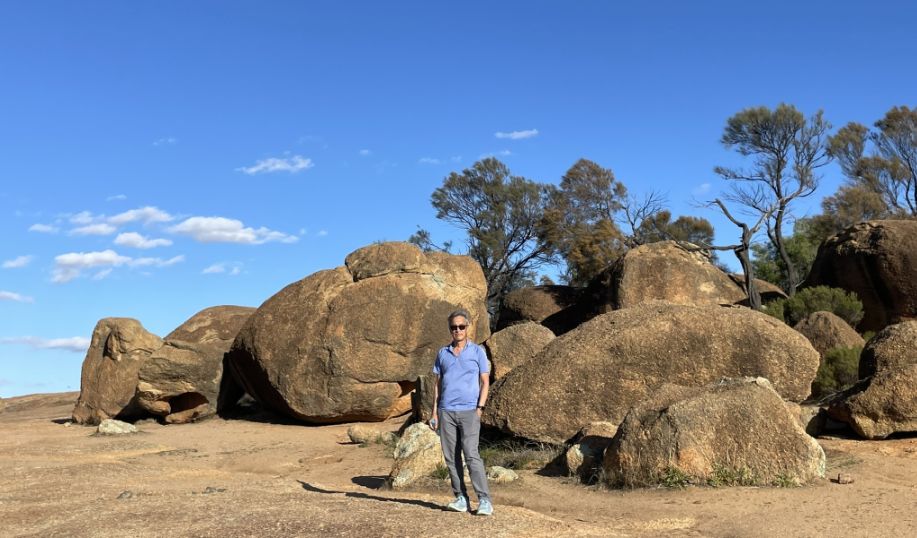

We followed the panel toward the Hyden Rock Walk, the path led us across the upper granite plateau where boulders have separated and rounded over time.

Hoa taking a moment to enjoy the beauty of this place.

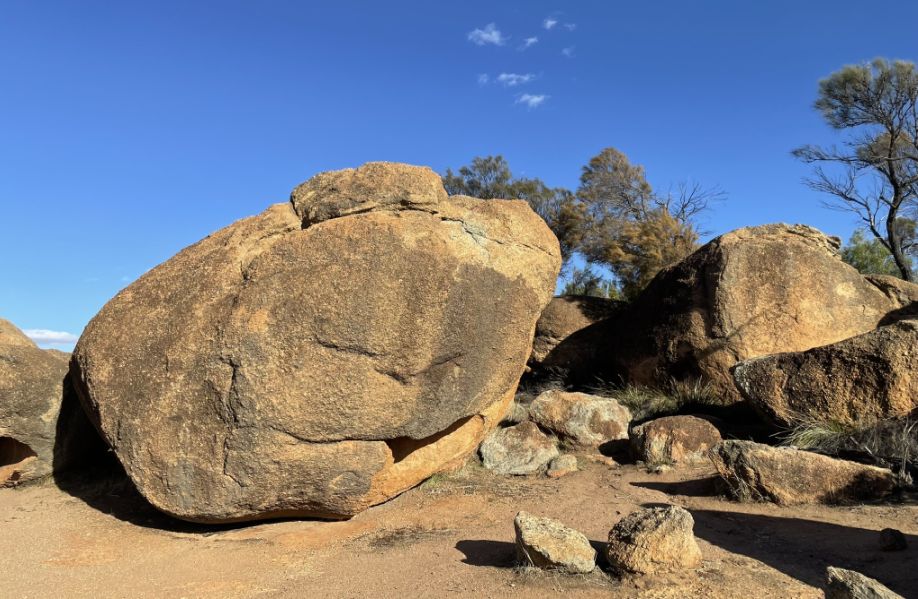

As we walked across the top of Hyden Rock, the path les us into a cluster of enormous granite boulders scattered across the summit. These rounded, clustered boulders located on the upper part of the Hyden Rock walk are fascinating granite formations whose history stretches back billions of years, formed through a combination of ancient geological processes and more recent weathering. Each cluster is like a piece of an ancient landscape frozen in place.

Hyden Rock is made of very old granite, more than 2 billion years in age. Inside this huge mass, natural cracks, called joints, formed deep underground when the granite cooled and contracted. Rainwater seeped into the joints, slowly softening the granite along these lines. The granite between the cracks was harder and resisted erosion, while the rock along the joints broke down.

With wind, water, and temperature changes, the corners rounded off, the edges softened, and each block became a smooth, dome-like boulder. These rounded forms are known as corestones.

Over time, the corestones separated into clusters, some remain tightly packed; others sit alone. Some pile into “towers,” while others spread across the surface like huge eggs.

|

|

The one on the left with a long, smooth edges that look almost like the

beak of a bird frozen mid-call. Walking among these formations feels like

stepping into a natural sculpture garden carved slowly by wind, water, and

time.

a

Each rock has its own shape and personality, some rounded like giant eggs, others stacked in layers like ancient ruins.

As we continued walking among the clusters of rocks, we came across several giant rounded boulders scattered across the summit.

One of them stands out immediately, a massive block shaped so perfectly that it looks like a head carved by nature itself, with smooth curves suggesting eyes, a nose, and the faint outline of a face. The way the shadows fall across its surface makes the features even more striking, as if the rock is quietly watching over the landscape.

The afternoon light catches their curves and shadows, making the shapes shift as we are moving around them.

Walking on the surface almost feels like stepping onto the lunar surface. The smooth, resilient rock, scarred only by long geological ages, is peppered with the grey, red, rounded clusters of boulders and giant hollowed tafoni (deep hollows and recesses ). These formations, sculpted by millennia of wind and chemical weathering, resemble the impact craters and strange, solitary mountains one might expect to find on the Moon.

The vast, sweeping dome of exposed granite creates an immense, open space under the enormous sky.

The Kennedia prostrata is a low-growing, matting or trailing ground cover, they add a brilliant splash of scarlet-red in the rugged landscape. It capitalizes on the minimal pockets of soil that collect in rock crevices and around the base of the boulders.

Its presence and survival on Hyden Rock are a testament to its remarkable adaptations to the harsh conditions of a granite inselberg..

Its wiry stems spread out, sometimes up to two or three meters wide, forming a dense, protective blanket over the thin, rocky soil. This helps stabilize the sparse soil and traps leaf litter and debris, slowly enriching the area it occupies.

|

|

Once established, it is highly

drought-tolerant.

Walking on Hyden Rock is pretty amazing, the view is also amazing as we are high above.

|

|

In the distant, we can see is one of the many dry salt lakes common in the Western Australian Wheatbelt region. These lakes are the remnants of ancient, massive drainage systems that once flowed across the continent millions of years ago. As the climate became drier, the water evaporated, leaving behind highly concentrated salt and gypsum beds.

The dense growth of trees and shrubs directly below and surrounding the rock is the vegetation adapted to the local environment.

We are now going back down.

|

|

That descent certainly gives you a sense of scale! Looking back up, you can really appreciate how tall that ancient granite monolith is about 50 feet high at its crest. Now that we are at the far end of Wave Rock and off the stairs, we moved from the high, weathered summit to the base, where the most famous feature is located.

At the very bottom edge of the Wave Rock base, you'll also see the concrete catchment wall. This wall was built in the early 1950s (extending the earlier 1928 wall) to collect the massive amount of rainwater that runs down the Wave Rock face. The water is then funneled into a reservoir, which historically provided the essential water supply for the nearby town of Hyden.

Walking along the base of that massive granite curve allows you to fully appreciate the scale and the sheer power of nature's forces that sculpted it.

|

|

The change in perspective as you walk from the end back toward the front allows you to notice the subtle details that make Wave Rock so captivating.

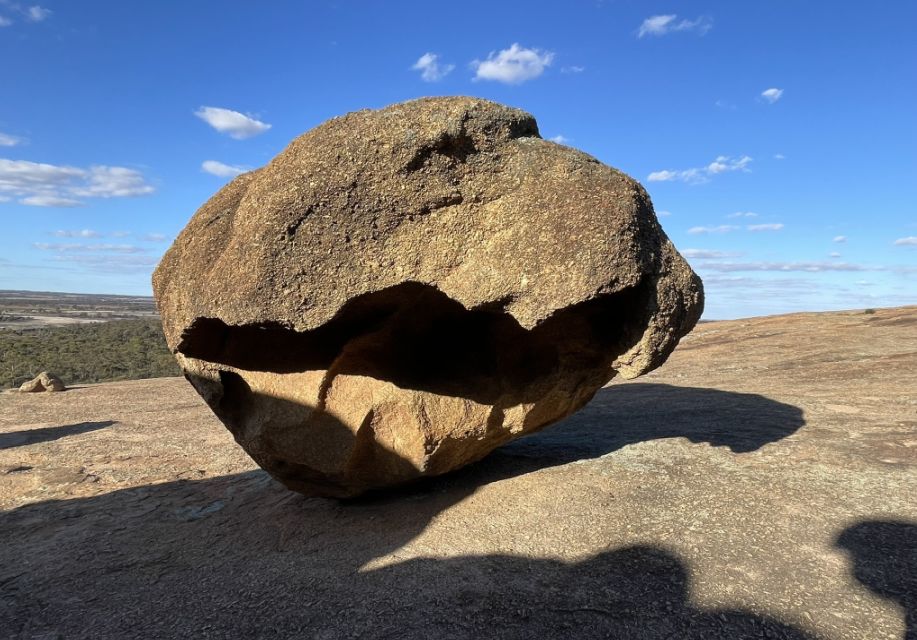

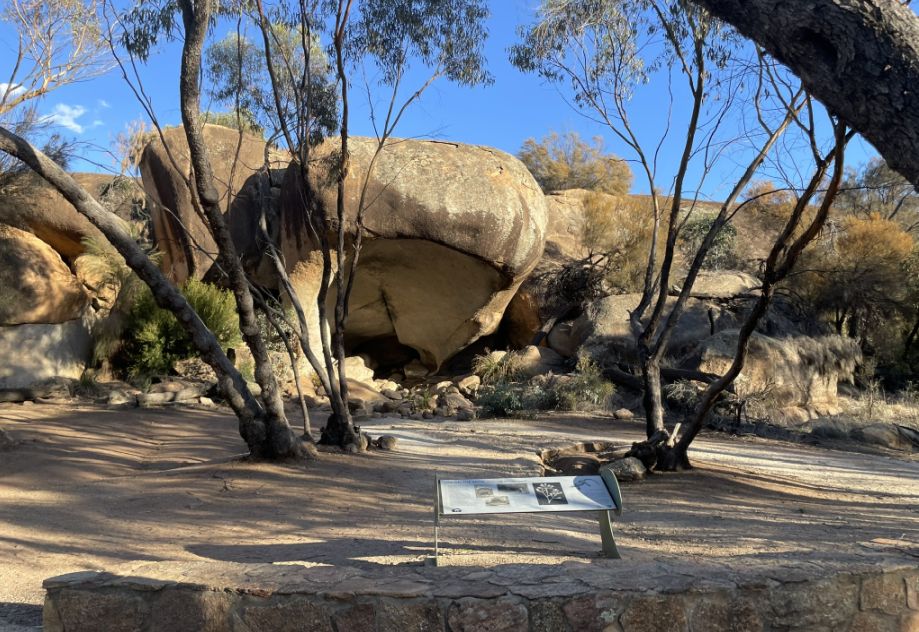

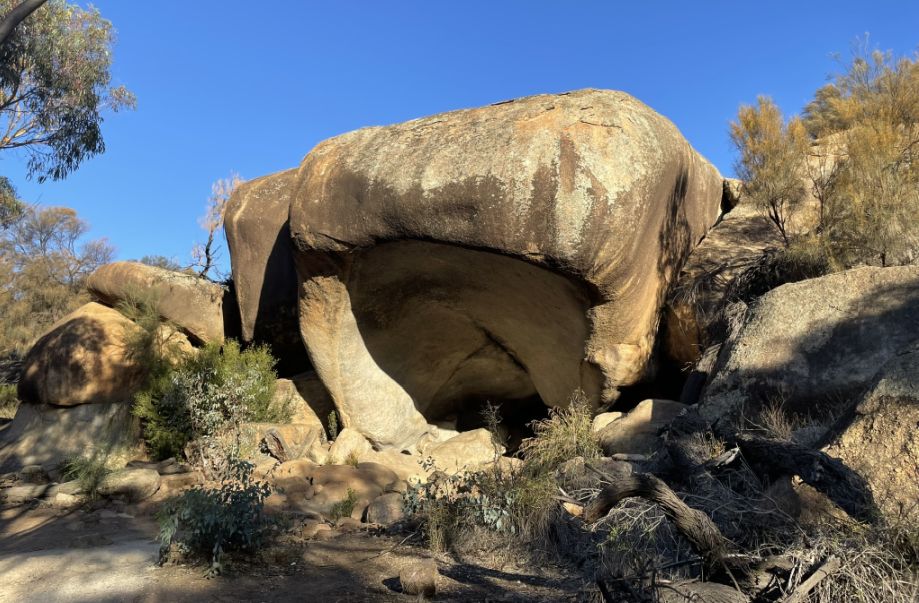

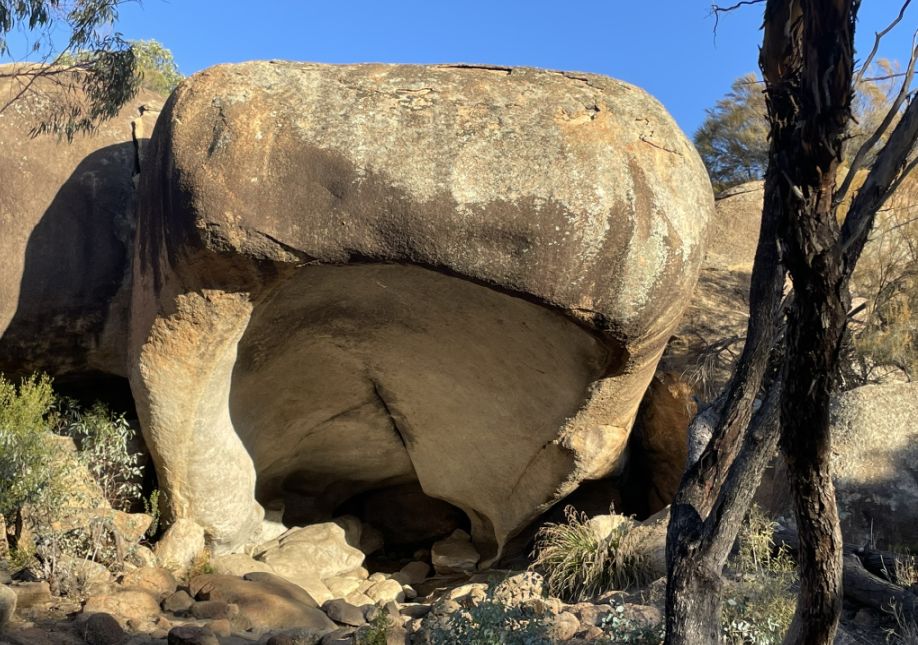

From the Wave Rock, our tour guide drove us to Hippo's Yawn, one of the iconic formations associated with Wave Rock. It is located approximately 0.6 miles east of Wave Rock.

It is connected to the main Wave

Rock car park and Wave Rock itself by an easy, well-marked walking trail.

Hippo's Yawn is a fascinating geological feature. It is a large, unusually shaped granite tor (an isolated rock outcrop) that resembles a giant creature's open mouth.

Hippo's Yawn is a granite cave, or a

large, shallow, gaping arch that has been eroded from the base of a massive

orange boulder.

The shallow cave is impressive in scale, measuring

around about 41 feet tall at

its mouth.

|

|

The rock is composed of ancient granite and is part of the same massive rock outcrop of Hyden Rock that also features Wave Rock.

I have to say that it does really looks like a hippo mouth.

|

|

Our tour is now over and we hopped on the bus. The sun was setting on the horizon, it was so peaceful.

Our tour guide passed the town of Corrigin, and made a brief stop to show us the Corrigin Dog Cemetery. It was created as a tribute to "man's best friend" and specifically recognizes the incredible value of working farm dogs to the survival and success of the local farming and sheep industry.

A striking feature of the site is the statue of a large dog, which stands as a

landmark and memorial to all the animals buried there.

The cemetery holds the remains of over 200 beloved

dogs.

The drive from Hyden back toward Perth is a significant journey, it's roughly 210 to 225 miles, taking around 3.5 to 4 hours. As the sun sets over the Western Australian Wheatbelt, the landscape we are passing creates one of the most memorable sights.

The land is generally flat, which allows you to us the entire massive arc of the sky. This lack of obstruction ensures the orange and red hues of the setting sun are fully visible, giving you that incredible orange glow.

The deep, rich colors of the sky contrast beautifully with the silhouettes of the remnant Eucalypt woodlands and the vast, harvested wheat and canola fields passing by our window, giving the scene a serene, almost painterly quality.

NEXT... Day 6-Last day in Perth/Bali