6 days in Perth, Australia- 5/22- 5/27/2024

| Day 1 Arrival |

Day 2 Elizabeth Quay Downtown Perth Freemantle |

Day 3 Rottness Island Rottness Island Continuation |

Day 4 Freemantle Markets Freemantle Prison |

Day 5

Wave Rock Day Tour Wave Rock/Hyden Rock |

Day 6 Last day in Perth |

Day 4-Freemantle Prison-5/25/2024

Fremantle Prison has one of the most significant and well-preserved convict

histories in Australia. The prison was built by convicts between 1852 and 1859

after the Swan River Colony requested convict labor to boost its struggling

workforce. The men who arrived on the convict ships were housed temporarily in

a work depot and then put to work constructing the massive limestone complex

that would become Fremantle Prison. By 1855, parts of the prison were already

in use, even as construction continued. After transportation ended, the

British transferred the prison to the colonial government in 1886, and it

became the main high-security prison for Western Australia for more than a

century. One of the most dramatic events was the 1988 prison riot, when

inmates set fires and caused major destruction while protesting poor living

conditions. This became a key factor leading to its closure in 1991, and after

its closure the WA state government embarked on a long-term conservation plan

to ensure the Prison’s preservation for future generations. Fremantle Prison

is one of the largest surviving convict prisons in the world today

The iron silhouette figures along the way symbolically represent the thousands of convicts and prisoners who lived and labored here. They’re meant to visually connect the modern city with its convict-built foundations. The iron sculptures are located on the Fairbairn Street entrance ramp, which is the main approach to the Fremantle Prison World Heritage site

It's often described as a life-size metal silhouette or an interpretive sculpture depicting the arrival of convicts. The artwork is a 45 ft. long, two-piece silhouette that depicts a group of life-size convicts walking up the ramp under the watchful guard of pensioner guards. It creates a haunting visual of the men's first steps into their long period of incarceration.

The Fairbairn Street ramp was originally constructed by convict labor using building rubble from the site. Historically, this ramp was the main pathway along which newly arrived convicts were marched from the convict transport ships at Fremantle Port to the prison gatehouse. The installation powerfully captures the harsh purpose of this route and the despair of the arriving convicts, giving visitors a tangible connection to the past before they even enter the prison itself.

We are now walking toward the Prison.

|

|

To our big surprise we saw Lisa, sitting there waiting to get in the next tour to the prison. It was totally a coincidence to see Lisa there so we all took the tour together.

|

|

The building's importance is recognized by its classification by the National Trust in 1974 and its entry into

Today, Fremantle Prison is one of the best-preserved convict-built sites in the world and is part of the UNESCO World Heritage listing for Australian Convict Sites. Many original features remain: the cell blocks, the yards, the gallows room, and underground tunnels dug by prisoners.

The two-story limestone Gatehouse of the main building at Fremantle Prison is designed to be imposing and formidable, perfectly reflecting its original purpose as a colonial maximum-security prison. Constructed primarily of local limestone, which was quarried on-site by the convicts themselves during the prison's construction in the 1850s. This material dominates the entire complex.

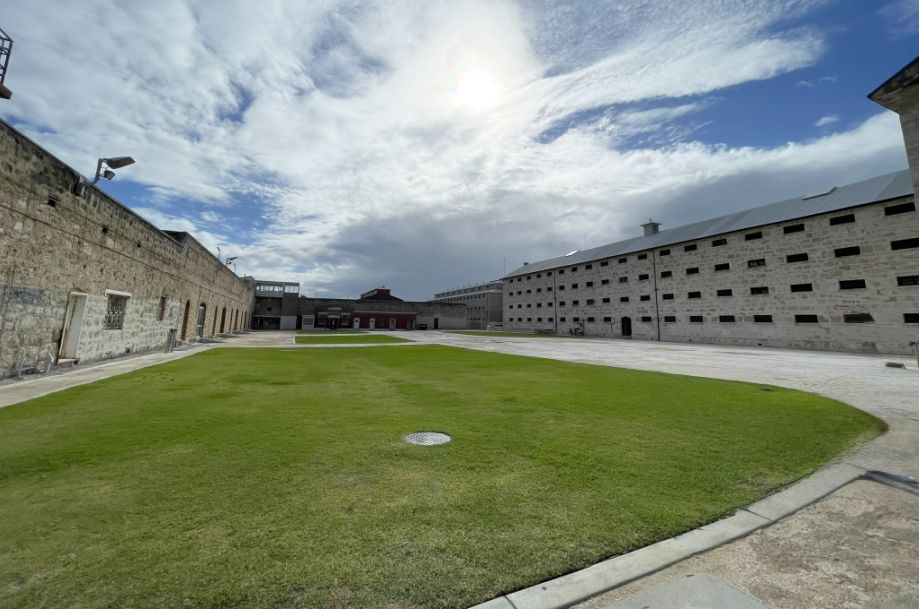

We took a guided tour and we were led into a court yard waiting for our tour guide to show up.

This is the view of the entrance of the Prison from inside the courtyard.

Here is our tour guide waiting next to big iron gate. This gate is part of the original 1850s entrance complex, forged by convicts in the early years of the prison’s construction. This gate marked the psychological divide between freedom and confinement. Once a prisoner stepped through it, they were in the controlled world of the prison system.

Much of the ironwork, including gates, locks, hinges, and grilles, were forged on-site by skilled convict blacksmiths. The gate is an example of their craftsmanship, built for durability and security rather than decoration. The gate has remained intact through riots, fires, and more than a century of harsh use. It’s one of the most recognizable items in the entry complex.

After passing the gate, we entered the Parade Ground, the large central courtyard inside the prison walls. Historically, this was the daily heart of the institution.

Prisoners lined up here morning and evening for roll call. It is also here that Public floggings and disciplinary hearings happened in this yard in earlier decades. In later years, this became the area where inmates could briefly exercise or socialize under strict supervision.

The scale of the courtyard is intentional, wide, exposed, and controlled. Guards had clear sightlines from multiple vantage points, and prisoners had nowhere to hide.

Standing there today, you can still feel how stark and commanding the environment was designed to be.

|

|

Stepping through that small red door is one of the most striking moments of the Fremantle Prison tour. It feels almost theatrical, one second you’re outside in the open courtyard, and the next you’re funneled through a narrow entry into the heart of the cell block. That dramatic contrast is exactly how it was meant to feel for prisoners.

This door was intentionally small and tightly confined, symbolizing the loss of freedom the moment someone entered the cell block. It also served a practical purpose: it allowed guards to control movement and made it harder for prisoners to rush through.

Once you step through, the entire interior opens up into the massive Main Cell Block, a soaring three-story structure designed in the mid-1850s by the same convicts who built the outer walls. Three tiers of narrow balconies run along both sides, each lined with small, identical cells. The central space is open all the way to the ceiling, allowing guards to see everything happening on every floor.

The block is built from local limestone, giving it that pale, rough, almost cold feel. This open vertical design was inspired by British “panopticon-style” principles, maximum visibility, minimum hiding places.

Iron staircases and catwalks connect the levels, all built by convict blacksmiths. Division 1 is one of the four key sections created within the Main Cell Block of Fremantle Prison, and it was primarily used to house the most challenging and dangerous prisoners. Division 1 is located within the original 1850s Main Cell Block, which is the longest and tallest cell block in Australia.

Our tour guide explaining that inside Fremantle

Prison, the lack of toilets in the cells was one of the most defining, and

degrading parts of daily life. Our guide mentioned the bucket, he was

referring to a system that lasted right up until the prison closed in 1991,

which is astonishing by modern standards. The stench inside the cell block

could be overwhelming, especially in summer.

Newspapers, former inmates, and inspectors repeatedly complained about Health

risks, Insects, Air quality, and loss of dignity.

|

|

Prisoners were locked in their cells in the late afternoon or early evening,

sometimes for up to 14 hours straight. During that time, they had no access to

a bathroom. If they needed to relieve themselves, they had no choice but to

use the bucket. Every morning after roll call, prisoners carried their buckets

out to a designated area called the slop trough.

There, they had to empty and clean them, often in long lines, with guards

supervising and the smell overwhelming.

|

|

Each original cell was tiny, about 5 ft. by 6.5 ft. (barely big enough to stretch out). Early convicts slept on hammocks; later prisoners got narrow iron beds. Ventilation was minimal, just small barred openings that barely let in light or air. In the late 19th century, the colony added skylights above the upper galleries to reduce the dungeon-like darkness.

When you stand inside the small cells and look at the floor, it becomes clear just how little room there was, and how confronting it must have been to live inches away from the bucket every night. It’s one of the most visceral reminders of how harsh prison life was here.

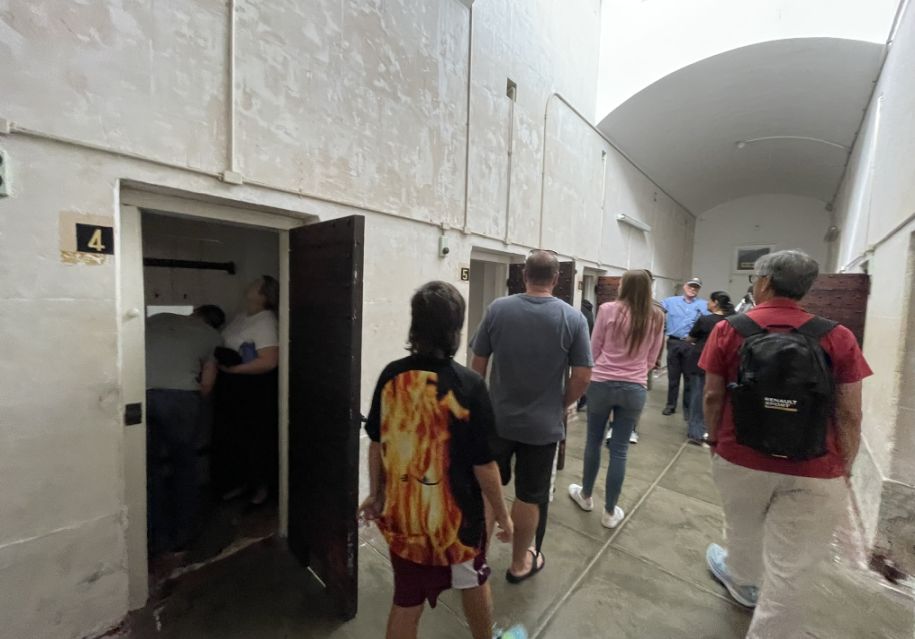

Our tour guide is now taking us to Division 2 is one of the most memorable parts of the main cell block because it lets you experience the space almost exactly as prisoners and officers once did.

Once we climbed the iron stairs, we stepped onto a narrow, exposed walkway called a landing, suspended above the central void. Historically: Prisoners lived on these upper levels in the earlier years. Guards patrolled along the opposite side to monitor behavior. The catwalks were deliberately narrow to prevent groups from clustering. Every noise, footsteps, whispers, movement, echoed throughout the entire block. From the railings, you can look straight down into the open space, seeing all three stories at once. That vertical openness was intentional: it let guards instantly observe activity on every level.

The way our guide positioned all of us in on one side of the landing and him on the other is part of demonstrating how the space was used and controlled.

By having us standing along one railing while he stands across the landing, our guide is showing the officer’s vantage point: watching, listening, and controlling movement from a position of safety.

It’s a powerful point in the tour because it shows how Fremantle Prison controlled not just prisoners’ bodies, but their movement, space, and even the way they could stand or gather.

Next, we were taken to the Fremantle Prison Chapel, one of the most significant and atmospheric spaces in the entire complex. It’s a place where punishment, discipline, and religion were all intertwined. Built in the 1850s, the chapel sits on the upper level of the main cell block. Unlike most of the prison, it has a softer, calmer feel, though its purpose was still deeply controlled.

|

|

Compared to the stark limestone cell block, the chapel offered more natural light, softer wood tones, a sense of quiet. This made the space feel almost otherworldly for prisoners. For many men, it was the only place inside Fremantle Prison where they saw color, decoration, or any kind of beauty.

In the 19th century, prisons strongly believed in “moral rehabilitation.”

Religious instruction, mainly Anglican (Church of England) was seen as a way

to reform the character of prisoners.

Attendance was often mandatory. Prisoners sat in strict rows under the watch

of guards. The chapel wasn’t only for Sunday services; it was used for daily

prayers, scripture readings, and moral lectures.

a

|

|

The tour takes us from the main Anglican chapel into a second, much more decorative space that surprises a lot of visitors. The iron gate with the red “C of E” (Church of England) emblem marks the official boundary of the Anglican-controlled area, and stepping past it leads you into what is often called the Catholic Chapel or Remand Chapel, a separate worship space created later in the prison’s history.

We are now in the Catholic Chapel. By the late 19th and early 20th

century, the prison population had shifted.

Many inmates were Irish Catholics or migrants from countries where Catholicism

was the majority. These men were not allowed to fully participate in Anglican

services, and tension grew over the lack of proper religious accommodation.

Instead of redesigning the original chapel, the prison converted an adjacent

room into a more decorated Catholic chapel.

Even though this chapel was created inside a harsh prison, it still carries those stylistic elements. The column drawings on the walls were added to give the illusion of architecture and sacred structure, despite being in a simple stone room. For Catholic prisoners, it was one of the few places in the entire prison where they were surrounded by beauty rather than stone, iron, and confinement.

We are now towards the end of the tour and we were taken to a very intimate look at how prisoners actually lived, and it shows how the prison changed over time, from the early convict era with hammocks to later years with tiny stone cells. This is the Early Convict Sleeping Quarters when Fremantle Prison first opened in the 1850s, the British government was still sending convicts to Western Australia. n those early years, there were now individual cells yet. Men slept in large communal rooms called association wards. Each convict slept in a hammock, slung from hooks in the timber beams. The hammocks were arranged extremely close together, shoulder to shoulder to fit as many men as possible. Hammocks were used because they were cheap, easy to remove, hard for prisoners to use as weapons, practical in rooms where the floor space was overcrowded. This setup only lasted in the earliest decades; eventually the prison switched to individual cells.

We are in Prisoner Artwork in Division 4/Remand Area with drawings that were created mostly in the 1980s and early 1990s, near the end of the prison’s life.

These artworks were made by prisoners who were given a little more freedom in the remand or protection units. Many of them used art for expressing faith, coping with Trauma, passing long hours, and seeking comfort during difficult times.

Some rooms have entire walls covered in drawings. Because Fremantle Prison closed in 1991, these artworks are now preserved as a striking reminder of the emotional and spiritual lives of the inmates, far more personal than the formal chapels.

We are now visiting the modern individual tiny cells.

|

|

When you walked into one of the individual cells, you experienced exactly what most prisoners lived in for decades. Just 5X6.5 ft. , limestone walls, The cells were intentionally sparse to reinforce discipline and uniformity.

This area is where you get to see and step in the Standard Fremantle Prison Cell.

|

|

The cell with the tiny food hatch with a small opening in the door, often called a “food slot” or “inspection hatch” was used for: passing food into the cell, checking on prisoners without opening the door, passing documents or messages, communicating while the prisoner remained locked inside.

In earlier years, food was carried down the corridors in metal tins, and prisoners received it through the hatch to prevent any contact or disorder. Some hatches were also used to cuff a prisoner’s hands through the door if they were considered dangerous.

Today, we visited three different eras of Fremantle Prison life: Convict era (1850s–1880s) with hammocks in large communal rooms, then the Colonial & state prison era (1880s–1960s) with small stone cells with basic furnishings, and finally the late prison era (1970s–1991) with expressive religious wall art, food hatches, and evolving cell layouts.

Seeing all of this gives us a unique, layered view of how thousands of men lived, slept, prayed, suffered, and survived behind those limestone walls for over 130 years. When you stand inside one of these cells, you feel the air change, more still, more claustrophobic. Together, these sections show the harshest side of Fremantle Prison, from discipline, to isolation, and harsh treatment of inmates.

NEXT... Day 5-Wave Rock day Tour