A week in Melbourne, Australia- 5/4- 5/10/2024

| Day 1

|

Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 |

Day 7-Downtown (CBD) Melbourne-5/10/2024

Today marks our last day in Melbourne, and we’re making the most of it by exploring the downtown area (in Australia Downtown is called CBD which means Central Business District). With only a little time left, we’re trying to see as much as we can, from the busy main streets to the tucked-away laneways that give the city its unique charm. Every corner feels like a final glimpse of Melbourne’s vibrant heart before we say goodbye.

Southern Cross Lane is one of those tucked-away pedestrian laneways that shows off Melbourne’s character beyond the main streets. As you step into it, you notice how narrow and intimate the space feels compared to the wide city boulevards.

|

|

Above, throught the glass ceiling you can see tall buildings, giving it that classic Melbourne laneway feel, a little hidden and secretive, but full of life once you step inside. It’s the kind of spot where office workers grab coffee, friends meet for lunch, and visitors discover cozy corners of the city.

The lane is lined with small cafés, eateries, and boutique shops, many with outdoor seating that spills onto the pavement. Bright signage, chalkboards with daily specials, and the hum of conversations create a lively, urban atmosphere.

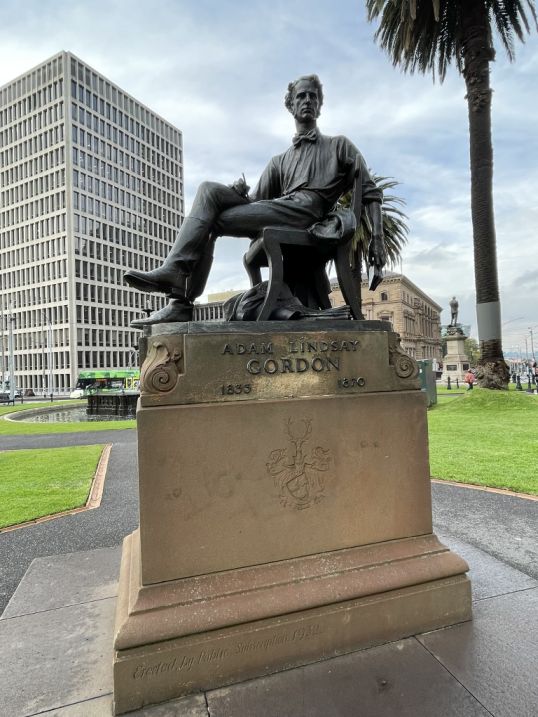

We are now are Gordon Reserve, It’s a small triangular park in Melbourne’s city center, just across from Parliament House.

The statue there commemorates Adam Lindsay Gordon, who was a famous Australian poet and also a skilled horseman. Gordon Reserve is often a quiet spot, framed by historic buildings, and it also includes a memorial fountain for Scottish poet Robert Burns nearby.

|

|

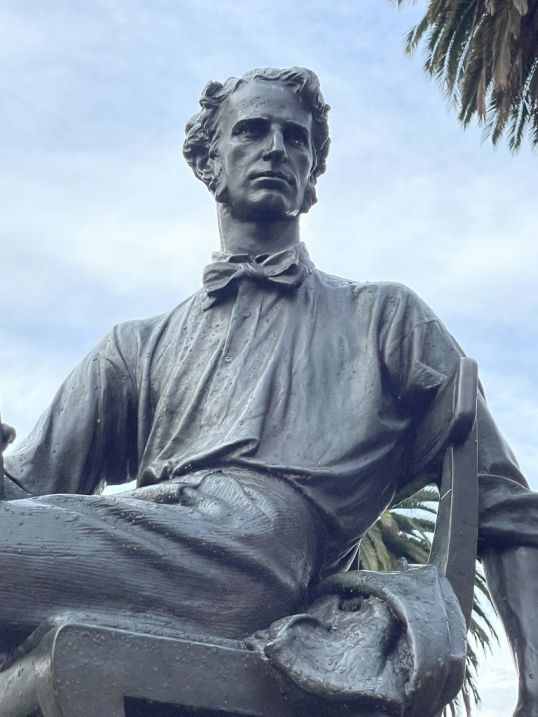

The statue of Adam Lindsay Gordon in Gordon Reserve is a striking bronze figure that honors Australia’s first poet to gain a significant reputation. It was unveiled in 1932 and shows Gordon, dressed in 19th-century attire, with a thoughtful yet resolute expression. His stance suggests both the reflective nature of a poet and the strength of a man who lived a rugged life as a horseman and drover before turning to literature.

Here you can see the statue facing the streets and surrounded by beautiful buildings.

Right beside the Adam Lindsay Gordon statue in Gordon Reserve is the Robert Burns Memorial Fountain, which adds another layer of history to the square.

The fountain was unveiled in 1904 to honor Robert Burns, Scotland’s national poet, who was deeply admired by Melbourne’s Scottish community. It’s made of granite with bronze features, and at its center stands a statue of Burns, looking outward with a book in hand. Around the base are four smaller bronze figures, each representing characters from his poems, like Tam o’ Shanter and The Cotter’s Saturday Night.

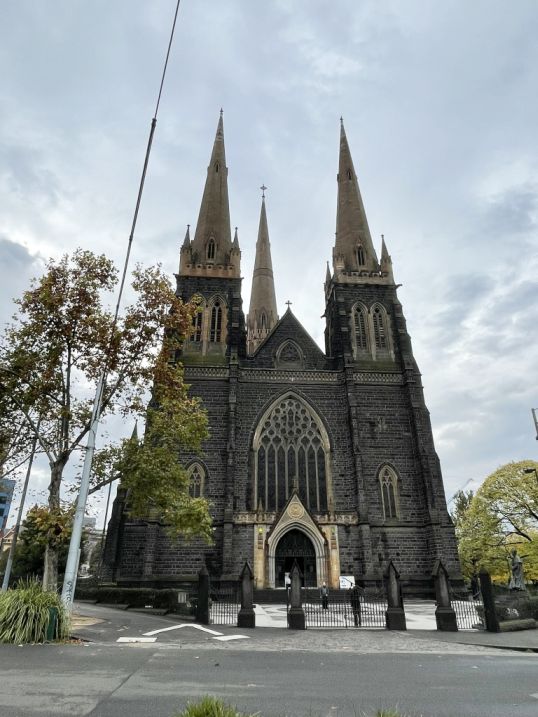

St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Melbourne has one of the most striking exteriors of any church in Australia. Built in the Gothic Revival style, its dark bluestone walls give it a dramatic, almost fortress-like presence, softened by the intricate sandstone detailing around windows and doorways. The façade is marked by soaring pointed arches, tracery, and a large rose window that catches the light beautifully.

|

|

What really dominates the skyline are the cathedral’s three spires: two tall spires at the front towers and a central spire rising even higher above the crossing. They give the whole structure a sense of upward movement, drawing the eye toward the sky. Around the sides, flying buttresses and tall lancet windows add to the richness of the design, while the surrounding gardens and lawns set the building apart from the busy city streets, making it feel almost like a retreat.

At the back of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, you’ll find a statue that adds to the sense of history surrounding the church. The sculpture you see is most likely one of the memorial statues dedicated to important Catholic figures in Melbourne. .

|

|

The most prominent is the statue of Archbishop Daniel Mannix, who served as Archbishop of Melbourne for nearly 50 years and was a towering presence in both the church and public life.

The bronze figure shows him standing tall on a stone pedestal, dressed in his clerical robes, with a calm but authoritative expression. The statue not only honors his role in shaping Melbourne’s Catholic community but also marks the cathedral as a living place of memory as well as worship.

As you step through the metal gates into St. Patrick’s Cathedral, there’s an immediate sense of transition from the busy city outside into a place of stillness and grandeur. The gates themselves are detailed with ornate ironwork, their dark metal forming elegant patterns that frame your entry.

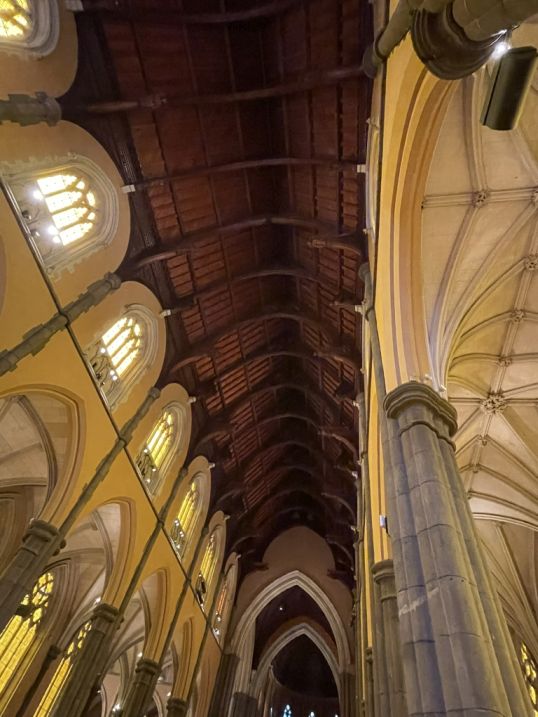

The moment you step inside St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the space feels vast and awe-inspiring. Tall stone columns rise in long rows, drawing your gaze upward and giving the interior a sense of rhythm and strength. Between them, arches soar gracefully, guiding your eyes toward the high ceiling above.

|

|

Straight ahead is the nave, the heart of the interior. Standing there you really feel the scale and harmony of the design. It stretches in a long, straight line from the great west doors toward the high altar, framed on either side by rows of clustered columns. These columns rise to support pointed arches, creating graceful arcades that separate the central space from the side aisles.

The light inside is soft and golden, filtering through stained-glass windows and bathing the stone walls in warm tones. It creates a gentle glow that contrasts with the coolness of the stone.

|

|

Above, the wooden ceiling adds warmth and texture, its dark timber panels richly carved and echoing the Gothic style while softening the grandeur with a touch of earthiness.

|

|

At the far end of the nave, the space opens into the sanctuary, crowned by a striking half-dome, or apse. The curve of the dome creates a natural focal point, drawing all attention forward to the high altar beneath it. Above, tall stained-glass windows rise within the apse, glowing with vivid colors when sunlight passes through. The windows depict saints and biblical scenes, their jewel-like reds, blues, and golds flooding the sanctuary with a radiant light that feels almost otherworldly.

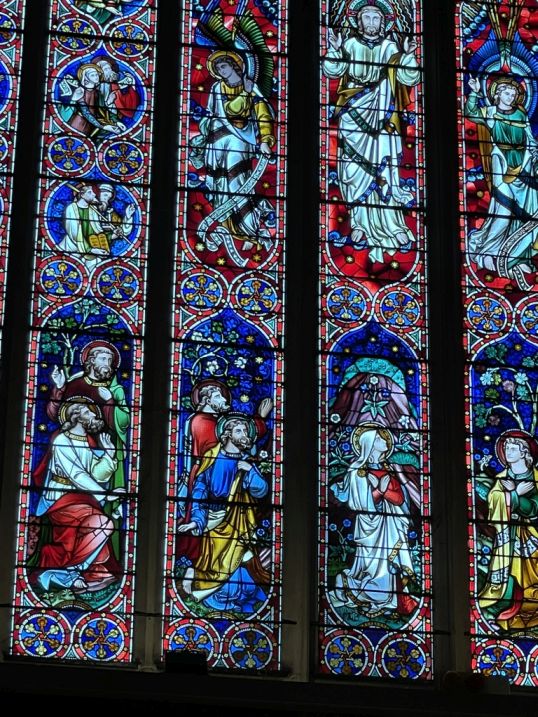

The side transept windows of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The cathedral has magnificent stained-glass windows in its transepts (the “arms” of the cross-shaped floor plan), and one of the most impressive is a tall window made up of seven panels, set into a soaring stone frame.

The sheer height and scale of the window allow light to flood into the side of the cathedral, casting colored patterns across the stone floor and columns. It also serves a symbolic purpose: the panels of glass act as a kind of “illuminated scripture,” teaching and inspiring through art.

|

|

These windows usually depict scenes from the life of Christ, important saints, or stories from the Old and New Testament, each panel forming part of a larger narrative.

We are now done with our visit and we are now leaving the Cathedral.

|

|

We made our way to Fitzroy, the atmosphere shifts to a livelier, urban charm.

|

|

Fitzroy itself is one of Melbourne’s most vibrant neighborhoods, known for its mix of bohemian energy, artistic murals, and quirky cafés tucked into Victorian-era buildings.

The streets are narrower and full of character, with a blend of old architecture and modern creativity. There a lot of vintage shops, boutique galleries.

Many of the buildings here are from the Victorian and Edwardian eras, often with ornate brickwork or decorative facades.

On the street level, you’ll usually find shops, cafés, bars, or small galleries, the everyday hustle of the neighborhood. The upper levels, though, are often quite different. Some are private residences or apartments, with people living above the businesses. Others might be studios for artists, offices for small creative companies, or even spaces that have been converted into boutique accommodations.

The mix of uses is part of what gives Fitzroy its lively, layered feel, you get the sense of both a working neighborhood and a lived-in community.

Fitzroy feels like a very different side of Melbourne which is a lot more casual, colorful, and buzzing with local life.

|

|

Arcadia Café, one of Fitzroy’s long-loved spots. It sits right along Gertrude Street, and its outdoor setup is part of what makes it so inviting.

The tables spill out onto the pavement, giving it a relaxed, European-style feel where people linger over coffee, brunch, or drinks while watching the street life pass by.

From the outside, the building has that characteristic Fitzroy look, a heritage façade with large windows, blending the old architecture with the modern buzz of people dining and chatting. The street is often lively here, with locals, visitors, and a creative crowd adding to the atmosphere.

The iconic Rose Chong Costumiers is a famous and beloved institution in Fitzroy, well-known for its vibrant and striking exterior. The building is painted in a distinctive, colorful style that often includes animal prints and other wild designs, making it instantly recognizable.

We are in the back of the Fitzroy beer garden which is essentially an outdoor galleries, layered with colorful murals, stencils, graffiti, and large-scale artworks that constantly evolve as new artists add their mark. The wall is covered in bold colors with everything from abstract designs to portraits, political messages, and a playful imagery. Street art here isn’t just decoration; it’s part of the cultural fabric of Fitzroy and inner Melbourne, known worldwide for fostering this kind of creativity.

|

|

The Fitzroy Beer Garden is quite a well-known spot in the neighborhood. It’s not a historic “garden” in the sense of trees and lawns, but rather a lively pub and social venue that’s especially popular on weekends and warm evenings.

We are walking on Brunswick Street, the main and heart of Fitzroy. It’s one of Melbourne’s most iconic strips, full of life at nearly any hour of the day. As we wander down the street, we noticed the buildings along the street are covered in graffiti and street arts

The pink wall with the “Melbourne Pride” message is one of Fitzroy’s most recognizable pieces of street art. It celebrates the suburb’s long connection with the LGBTQ+ community and its role as a hub for inclusivity, activism, and self-expression. The bold pink background immediately grabs your eye, while the “Melbourne Pride” text radiates a sense of celebration and belonging. Around it, you’ll often see other murals and graffiti layered nearby, which makes the wall feel like it’s part of an ongoing conversation, one where artists and locals affirm Fitzroy’s reputation as a place where diversity and creativity are embraced.

|

|

We stumbled on 2T cafe, a Vietnamese sandwich shop and we ordered a crispy pork sandwich and a Vietnamese coffee. It turned out to be one of the best crispy pork sandwich we ever had.

We are now leaving Fitzroy and heading back to the CBD (City business center).

Melbourne’s iconic green and yellow trams is one of the city’s most recognizable symbols. They’ve been running since the early 20th century and are an everyday part of life here, carrying locals and visitors through the city streets. The classic ones are called W-class trams, introduced in the 1920s. With their deep green bodies, yellow trimmings, and wooden interiors, they’ve become heritage icons. Today, many have been retired, but you’ll still see some in service, especially on the City Circle Tram (Route 35) which is a free tourist tram that loops around central Melbourne. Inside, they have timber seats and brass fittings, giving a nostalgic feel of old Melbourne. Beyond their vintage charm, Melbourne’s tram network is the largest in the world, and the green-and-yellow colors are instantly recognizable — so much so that the trams are often featured in postcards, murals, and souvenirs.

The ACA Building was built in 1935–36 as the Victorian headquarters for the Australian Catholic Assurance, a commercial insurance company that served the Catholic community. It was designed by the architectural firm Hennessy & Hennessy, which had strong connections with Catholic institutions.

|

|

The building is heritage-listed (by both the City of Melbourne and the National Trust), recognized as one of the more important examples of Art Deco/inter-war architecture in Melbourne.

The building is located at 118-126 Queen Street, the façade is clad in Benedict Stone, which is an artificial stone product. It was unusual at the time, because many Art Deco buildings used cement render or faience. Benedict Stone gives the building a striking look. From the base to the top, the Benedict Stone shades from darker at the bottom to lighter near the top. This adds to the tall, uplifting feel of the building.

Walking into the ACA Building feels like stepping back into Melbourne’s glamorous interwar era. The lobby was designed to impress, not just as an entrance, but as a statement of prestige and confidence. The first thing that strikes you is the rich use of materials: dark polished marble cladding the walls, gleaming metal details on doors and signage, and heavy plaster cornices overhead. The lighting is soft but dramatic, with original Art Deco light fittings that cast a warm glow across the space, picking up the shine of bronze and stone.

The ceiling of the ACA Building’s lobby is one of the features that makes the space feel so opulent and distinctly Art Deco. It is bold geometric patterns and stepped plasterwork that echo the vertical lines of the building’s exterior. The plaster cornices are heavy and layered, almost sculptural, creating a sense of rhythm as they run around the edges of the room.

|

|

Set into this framework are the original light fittings, which hang or are recessed in such a way that they wash the ceiling with a warm glow. The light softens the sharp geometry, so the ceiling feels both dramatic and elegant. When you look up, you can see how the designers used height and ornamentation to make the lobby feel lofty and grand, even though it’s not a vast space.

The proportions are grand, with the entryway soaring upward so you feel lifted as you come inside. Decorative moldings, geometric patterns, and finely worked details all combine to give the sense that no expense was spared. Even the smallest elements, like curved balustrades and etched glass that add to the richness.

The huge clock set into the archway is both decorative and practical, a reminder of the building’s role as a bustling office space in its heyday. Framed within the arch, it feels almost like a focal point, timekeeping elevated to an architectural feature. In the 1930s, this would have symbolized order, progress, and modernity, values the company wanted to project.

You can also see in the hall way, the black and white lamps are classic Art Deco. Their bold contrast and geometric shapes echo the overall design of the building.

|

|

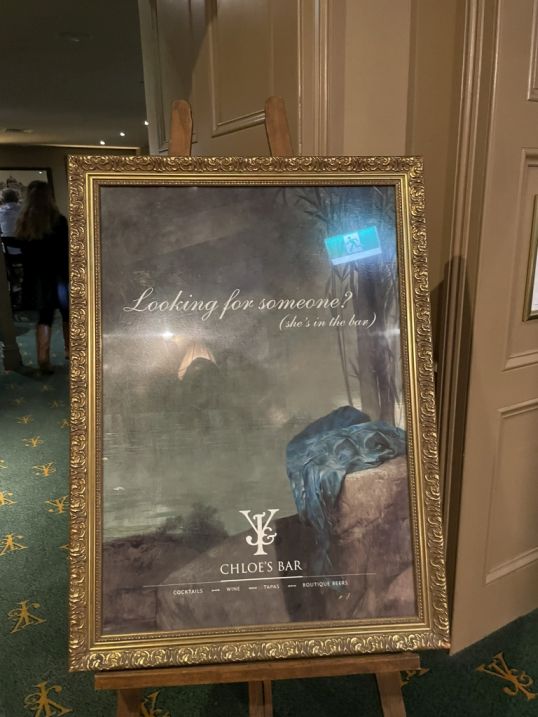

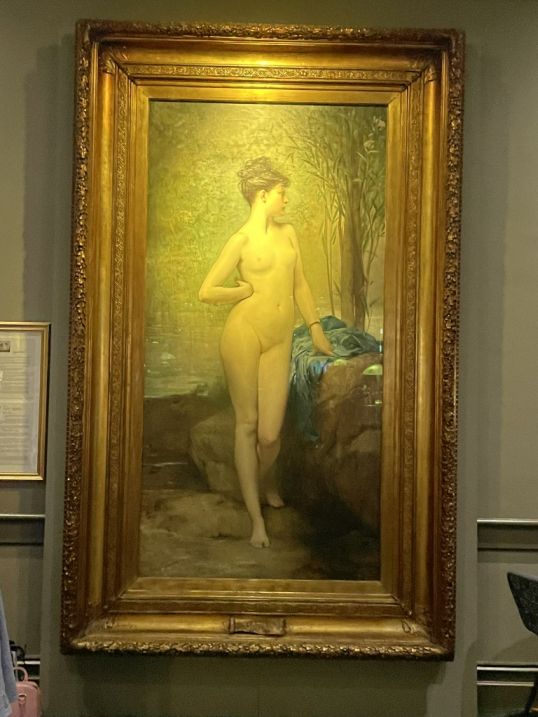

We are now at the Young and Jackson Hotel , home to the famous "Chloé" painting. It has a fascinating and controversial history.

"Chloé" is a large nude oil painting by French academic artist Jules Joseph Lefebvre, completed in 1875 in Paris. The painting made its debut at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1875 to critical praise. "Chloé" was exhibited at the 1879 Sydney and 1880 Melbourne International Exhibitions, where it won major awards. A Melbourne surgeon, Dr. Thomas Fitzgerald, bought the painting for 850 guineas in 1880.

In 1883, Fitzgerald

loaned "Chloé" to the

National Gallery of

Victoria.

"Chloé" became a beloved icon and a good-luck ritual

for Australian soldiers, particularly during World War I and World War II. It

was a traditional place for "diggers" to have a last drink before heading off

to war and a first drink upon their return.

|

|

A famous story involves a soldier,

Private A.P. Hill, who was killed in action in WWI.

The Prince's Bridge Hotel is

the original name of the historic pub in Melbourne now famous as Young and

Jackson Hotel.

NEXT... Dinner at Bottega