A week in Melbourne, Australia- 5/4- 5/10/2024

| Day 1

|

Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 |

Day 5-Phillip Island day tour -5/8/2024

Penguin parade

After the bus dropped us off, we made our way toward to visitor center and to the Penguin Parade.

From the parking lot, we walked into the visitor center, a ultra modern

building and sleek glass-and-wood building that blended into the coastal

landscape. The building has a

striking, often described as "star-shaped," environmentally sustainable

design.

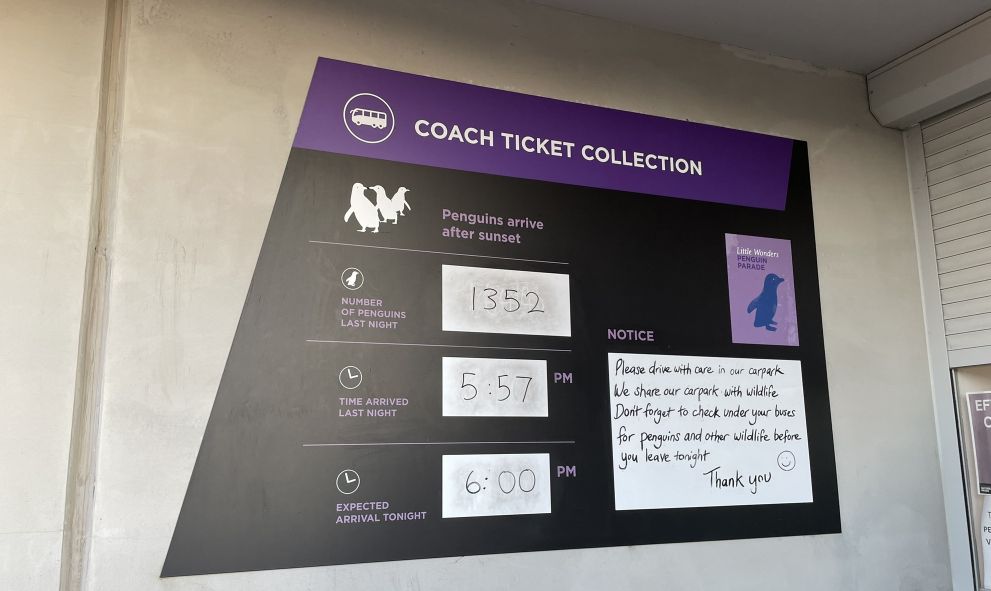

Tonight they are expecting the Penguins to arrive on the beach at 6:00pm

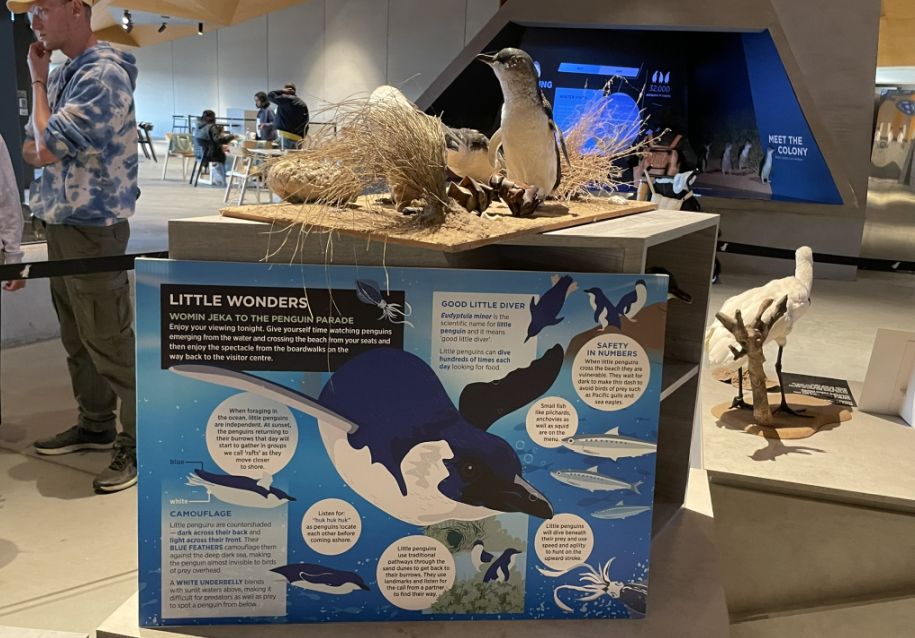

Inside, there were interactive displays about the little penguins, their habitat, and the wider marine environment. Large windows looked out over the dunes, giving us a first glimpse of the wild setting where the penguins make their burrows.

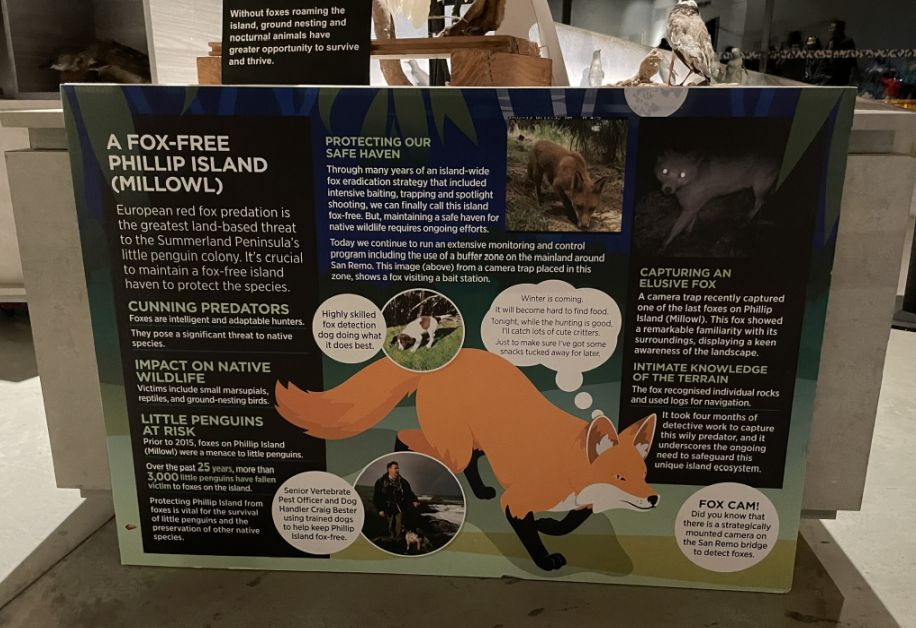

European red foxes were introduced to Phillip Island in the early 1900s, originally for recreational hunting. Over time the foxes preyed heavily on native wildlife. In particular, little penguin (also called fairy penguin) colonies were decimated. By the 1980s, nine of Phillip Island’s ten penguin colonies had become extinct. The last remaining colony on the Summerland Peninsula (where the Penguin Parade is) was under serious threat.

While control efforts go back decades, a coordinated Fox Eradication Strategy was formally put in place in 2004. From the mid-1980s onward, over 1,000 foxes were removed over 20 years through earlier control actions, but still foxes persisted. By end of June 2012, population estimates had dropped significantly to about 11 foxes left (in one survey) in the worst-affected area. Finally, Phillip Island was officially declared fox-free in 2017 after about 25 years of sustained effort.

Surveillance: Use of detection dogs, camera traps, night-vision equipment, regular surveys of known or possible fox habitats. Landowners, tourists, local residents encouraged to report fox sightings. There’s a hotline (0419 369 365) for reporting.

Rapid response to incursions: In 2022 (for example), a fox was confirmed on the island after a number of chickens were killed. Detection and trapping efforts (including using detection dogs) managed to locate and remove that fox.

The white bird you see is a Royal Spoonbill. While the penguins are the main

attraction, Phillip Island is a significant area for many water birds and

shorebirds, and the Royal Spoonbill is a well-known resident.

Since fox-related mortalities on the Summerland Peninsula stopped (for the little penguins) the penguin colonies have been much safer from land predators.

Recovery of other native ground-nesting or burrowing species has been facilitated. The eradication has allowed reintroduction of species that had been lost due to predation, such as the bush stone-curlew which is being released on Phillip Island now that foxes are gone.

|

|

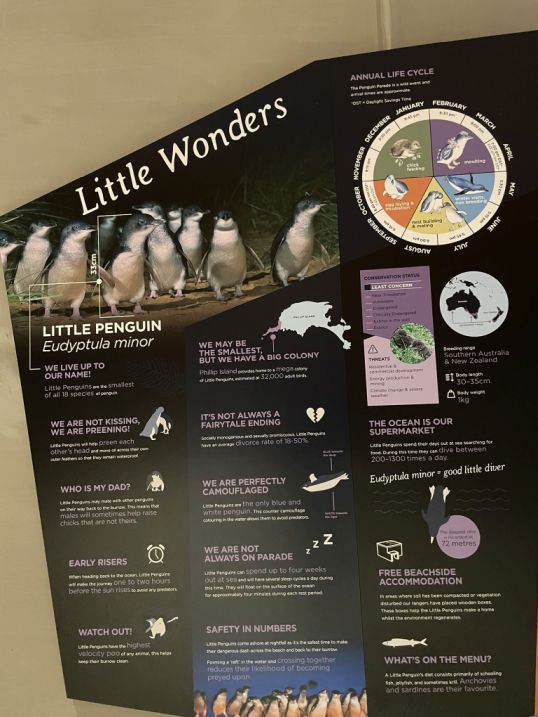

These penguins are little penguins (also called fairy penguins). They are the smallest species of penguin in the world with a height of about 12-13 inches tall and their weight is about 2 to 2.5 pounds. So even as adults, they stay very small, much smaller than the larger Antarctic penguins like emperors or kings. Their compact size is perfectly suited to burrowing on land and darting quickly through the water to catch fish.

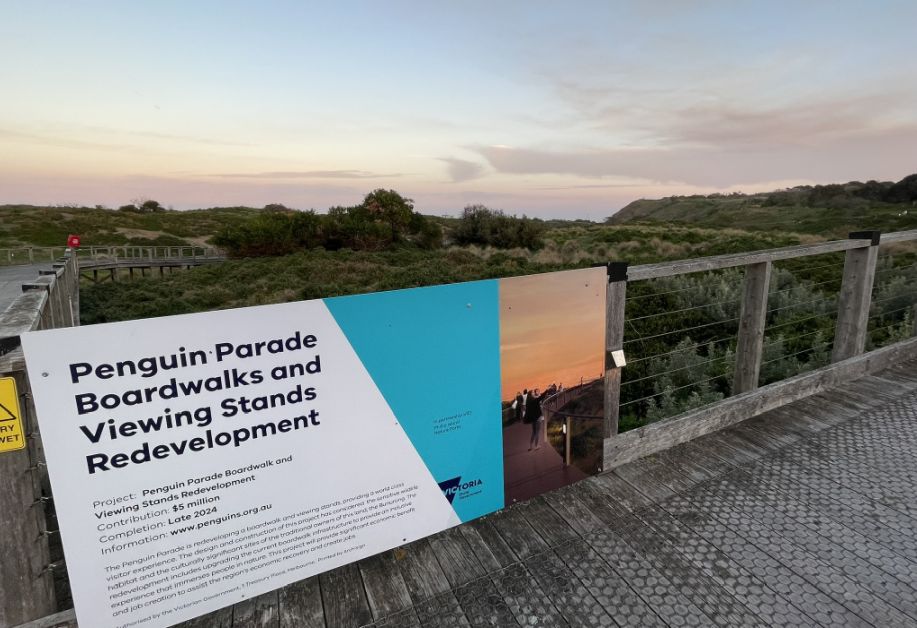

As we left the visitor center we followed wooden pathway to get to the beach.

The boardwalk winds gently through low coastal scrub and sandy dunes, keeping visitors raised above the fragile habitat where penguins dig their burrows. Along the way, you might spot the little entrances to those burrows tucked beneath vegetation or see seabirds circling overhead.

We walked further down the viewing platform, taking in new angles with each step.

|

|

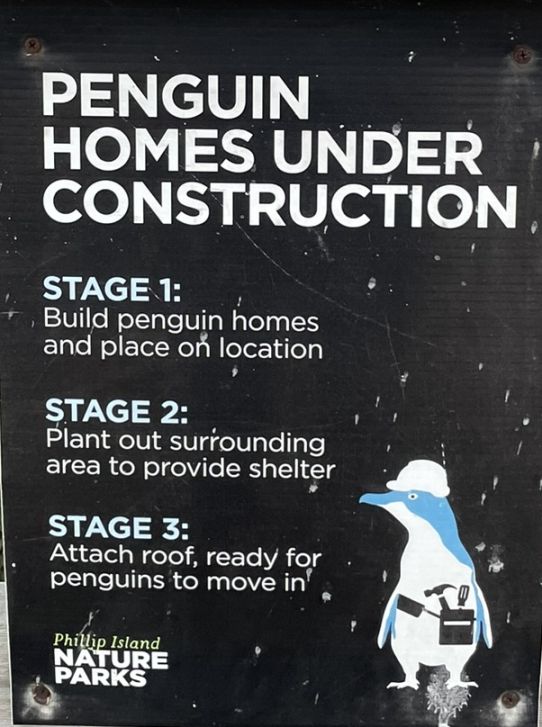

On Phillip Island, rangers and conservation staff sometimes build artificial penguin burrows to support the colony. These are small wooden or plastic nest boxes, placed in the dunes or among vegetation, that provide safe, dry spaces for the penguins to breed and shelter. They’re especially helpful in areas where natural burrows have been damaged or lost due to erosion, vegetation changes, or past human activity. This sign means that the park’s wildlife team is actively installing or repairing these burrows. The goal is to give the penguins extra protection and help the colony grow.

As we stepped onto the viewing platforms, the sea stretched out before us, with rugged rocks on either side catching the last golden light of the evening.

We are all waiting for the penguins to return from their day at sea, their arrival is estimated to be at 6:00pm tonight. The little penguins on Phillip Island emerge from the waters of the Bass Strait. The Bass Strait is the body of water that separates the island of Tasmania from the Australian mainland (Victoria), and Phillip Island is located on the edge of it. They also sometimes forage in the nearby Port Phillip Bay.

The beach stretches on a pale sandy beach that slopes gently into the the Bass Strait. The water is tinged with the colors of dusk as waves roll steadily ashore.

The wooden viewing platforms are slightly raised, giving everyone a clear view without disturbing the penguins’ natural pathways.

We are all very excited to be here and waiting for the penguins to emerge for the beach.

|

|

We met Thuy and her daughter while there. They are from Perth visiting. We ended up visiting her and her familly in Perth later on.

As everyone settles onto the viewing platform, a hush falls over the crowd. A guide steps forward and begins to speak softly, explaining what to expect. They remind visitors to keep still, stay quiet, and avoid using cameras with flashes so the penguins won’t be frightened. The guide shares a few fascinating details, how the penguins spend the whole day fishing at sea, sometimes swimming many miles, and then return together in little groups, known as "rafts", just after sunset.

We are not allowed to take pictures but the guide told visitors to download from their website. All the pictures of the penguins you see here are downloaded from their website but they represent very well what we witness seeing the penguins emerging from the ocean to the shore.

The Emergence (first 20-30 minutes):

The first small groups of penguins ("rafts") emerge from the water shortly

after sunset (the exact time varies greatly by season-our time was 6:00pm).

We watched in awe as they make their nightly journey past the dunes and into their burrows, the same ancient ritual they have carried out for generations.

From the platform, we followed the little penguins with our eyes as they make their way inland.

Some march with determination straight up the beach, while others pause, shaking off seawater or calling to their companions before hurrying along. Their tiny webbed feet leave neat trails in the sand as they head toward the dunes.

Little penguins walking on the sandy beach to reach their burrows.

The fairy penguin is the smallest species of penguin in the world, but despite their tiny size, they are sturdy little seabirds, perfectly adapted to life both on land and in the ocean. Their plumage is a striking contrast: the feathers on their back and head are a deep slate-blue, almost shimmering in the light, while their bellies are snowy white. This coloring is a form of camouflage, dark above to blend with the sea from above, and light below to blend with the sky when seen from underneath in the water.

They have short, stubby wings shaped like flippers, which they use to “fly” through the water with quick, graceful strokes. On land, they waddle in a slightly comical but determined way, their small feet carrying them from the sea to their burrows. Their eyes are large and silvery, giving them keen vision at dusk when they return from a day of fishing. Fairy penguins are social creatures, nesting in colonies and often calling out to each other with distinctive trills and squawks. Each penguin’s call is unique, helping mates and chicks recognize one another in the noisy, crowded colonies. Though they may look delicate, these little birds are tough survivors, braving the open ocean daily and returning faithfully to their burrows each night.

Once the first groups of penguins emerge from the sea and begin their waddle up the sand, the viewing experience doesn’t end there. Visitors can continue watching them by following the boardwalk platforms that wind through the dunes. The pathways are raised to protect the fragile habitat, but they bring you surprisingly close to the penguins as they make their nightly journey inland.

Once the first groups of penguins emerge from the sea and begin their waddle up the sand, the viewing experience doesn’t end there. Visitors can continue watching them by following the boardwalk platforms that wind through the dunes. The pathways are raised to protect the fragile habitat, but they bring you surprisingly close to the penguins as they make their nightly journey inland. Walking along the platform, you see penguins just a few feet away, some slipping under the boardwalk, others crossing right beside it to reach their burrows. The design of the pathways means you can follow the penguins without disturbing them, almost as if you’re traveling alongside them on their return home. It feels like being part of a quiet procession: people moving carefully on the platforms above, and the little penguins shuffling determinedly below, each one making its way back to the safety of its burrow for the night.

Once they reach the grassy slopes, the penguins fan out, following well-worn paths that wind through the vegetation. The air is filled with the soft sounds of their calls which is a mix of trills and squawks as they greet mates or signal to chicks waiting inside.

The Waddle to the Burrows (Next 30-60 minutes):

Once you leave the main beach viewing stands and walk back along the

boardwalks, you get the best view of the parade

as the penguins are all around you.

Even though hundreds of them arrive on the beach together, each bird knows exactly where its burrow is hidden among the dunes.

They use a combination of memory, sight, and most importantly, sound. Penguins recognize the unique calls of their mates and chicks. When they return from the sea, they often call out, and their partners or chicks answer back from the burrow. This back-and-forth helps them locate the right nest, even in the dark and in the middle of a crowded colony.

We spent about one to one-and-a-half hours watching the penguins, from the time the first groups arrive until they are deep into the colony along the boardwalks. Park rangers will gently usher visitors out after that time to leave the penguins in peace for the rest of the night. Here we are back at the Visitor center.

"Succour" (the word): This is an old-fashioned word meaning assistance and support in times of hardship and distress. The sign is a plea or a statement about the need to help the marine wildlife.

The blue birds, and the seals are all linked to the marine environment and conservation focus of Phillip Island Nature Parks.

Australian Fur Seals are highly susceptible to entanglement in fishing nets, plastic strapping, and other marine debris, which causes them immense suffering. Phillip Island Nature Parks conducts research and rescue programs for entangled seals.

While you may be seeing an artistic representation, the local seabirds, like the Little Penguins and Short-tailed Shearwaters, are also heavily impacted by plastic pollution, either through ingesting microplastics or getting tangled in larger debris.

|

|

A map of penguins around the world.

The visit is now over and we are now leaving the Visitor center.

At night, the interior lighting casts a warm, inviting glow through the many long, narrow windows and main entrance. The light inside highlights the exposed timber structure, especially the high, glulam beams, creating a welcoming contrast with the dark exterior.

Our bus is waiting for us to take us back to Melbourne. The drive from Phillip Island (starting at the Penguin Parade Visitor Centre) back to downtown Melbourne (CBD) is approximately 91 miles and takes about 2 hours.

NEXT... Breakfast/ Arts center Melbourne