9 days in Japan- 6/23- 7/1/2024

Day 5-Fukushimagata, Niigata-6/27/2024

Today we are heading out to Fukushimagata, a beautiful natural area just outside central Niigata, a place where wide open water, rich marshland, and abundant wildlife form one of the most peaceful and evocative landscapes in the region. This region is considered a natural treasure and is sometimes referred to as a wildlife sanctuary and nature park, a protected area where more than 220 kinds of birds and over 450 kinds of plants have been recorded.

After getting off the train, the landscape opened up. Yellow flowers grew everywhere along the roadside and in the fields, forming loose, cheerful patches that glowed in the sunlight.

Beyond them stretched vast rice fields, flat and endless, their young green shoots standing in neat rows. The horizon felt far away, uninterrupted by buildings, just sky, fields, and light.

|

|

While Fukushimagata is world-famous for its "sea of yellow" rapeseed flowers in April and May, those would have long faded by late June.

When we reached the visitor center, it was still too early to go inside, so we wandered around the surrounding paths. That quiet waiting time turned out to be a gift.

We crossed Habataki-bashi Bridge, a simple span over a narrow a man made canal.

Below us, the water was almost perfectly still, dark and glassy, with clusters of floating green plants resting on the surface.

Nothing moved except the occasional ripple from an insect or a drifting leaf. The silence was so complete that even our footsteps on the bridge sounded loud for a moment.

This canal isn’t merely scenic, it’s a working part of how water has been managed and shaped for agriculture here for many decades. Together with rice fields, wetlands, and irrigation ditches, it forms part of the hydrological network that keeps the floodplain fertile and productive.

This area is so quiet. There are nobody else beside us. In the distance, we could see several small bridges.

|

|

Wild chamomile flowers in bloom.

Following the river path

This Bridge is a famous vantage point for birdwatchers and photographers. Looking down into the canal in June, we are seeing a highly protected "ecotone"—the transition zone between land and water that supports over 450 species of plants.

|

|

The Cogongrass plants are topped with fluffy, silvery-white seed heads that look like soft feathers. They create a blurred, dreamlike border to the path, swaying in unison as we passed.

|

|

Dancing along the path is the Greater Quaking Grass. In Japan, it’s known as Kobansou, named after the Koban gold coins of the Edo period. As the breeze rolls off the lagoon, these little "lanterns" tremble and quake, catching the light like spilled treasure.

A hilly area filled with Cogongrass plants.

|

|

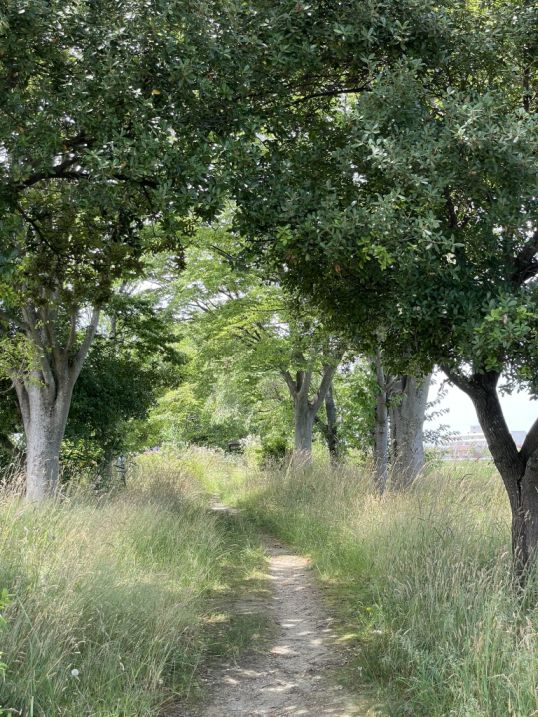

As we moved further, the paved path gave way to a rustic dirt road. Here, the landscape shifted. On either side, the grass grew tall and wild, and a canopy of towering green trees. We were walking through a cool, shaded tunnel. It was a brief, refreshing escape from the June sun, with the sound of cicadas just beginning their seasonal hum in the branches above.

The road narrowed into a simple path, and suddenly the landscape opened into rice fields in every direction. The paddies were a deep, vivid green, each plot carefully squared and edged with narrow earthen banks. Young rice plants stood in perfect rows, their thin blades catching the sunlight and swaying slightly in the breeze, like soft green waves moving across the land.

|

|

Niigata is one of Japan’s most famous rice-growing regions, and scenes like this are the foundation of that reputation. The flat land, clean water from rivers and wetlands, and careful farming traditions make these paddies not just farmland, but a defining part of the landscape and culture.

The paddies were a deep, vivid green, each plot carefully squared and edged with narrow earthen banks. Young rice plants stood in perfect rows, their thin blades catching the sunlight and swaying slightly in the breeze, like soft green waves moving across the land.

In late June, this is the height of the growing season in Niigata. The seedlings have already been transplanted from nursery beds and are settling into the flooded fields, drawing nutrients from the water and rich soil below.

For now, the fields are quiet, but beneath the surface there is constant life, water flowing slowly through hidden channels, roots spreading, insects moving between stalks.

A narrow dirt path ran slightly higher than the paddies, like a thin ribbon laid between sheets of water.

|

|

Walking on it felt delicate, almost like balancing on the edge of the fields. On both sides, young rice plants rose straight out of the shallow water.

The path was just wide enough for one person, packed hard by farmers’ boots and small machines, built to reach each plot for planting, weeding, and checking the water levels. With water quietly surrounding the trail and rice stretching outward in perfect rows, the world felt hushed and open at the same time, sky above, water below, and growing life on either side.

Near the path stood a small, plain building, almost like a shed, with several machines lined up behind it and an enclosed pond beside them. This was not a home, but a local irrigation station. The machines are water pumps and control units. Farmers use them to move water between the canal, the pond, and the surrounding rice paddies. Rice cultivation depends on carefully controlled water levels, so these stations regulate how much water flows into the fields, when it is drained, and how it circulates during different stages of growth.

We are now heading toward the Visitor and observation tower.

From the upper floor of the visitor center, the landscape opened wide and flat in every direction. Ahead is a view of the wetland spread out in quiet greens and silvery water, edged by a small parking lot beside the canal.

From the upper floor, the wetland feels calm, wide, and almost weightless.

Sheets of shallow water reflect the sky like pale mirrors, broken only by soft islands of reeds and grasses. Narrow channels weave through the plants, catching the light as they slowly drift toward the canal.

There is a sense of openness here, the land low and flat, the horizon far away where water, sky, and greenery meet without sharp boundaries. Looking down from above, the wetland doesn’t feel wild or harsh, but gentle and beautiful.

|

|

As we moved around the circular deck, a neat row of houses lined the opposite bank.

Closer view of a cluster of the houses in this area.

A simple bridge connected this side to the rest of town.

Farther away, more bridges crossed the waterways like thin lines, linking clusters of low buildings scattered across the plain.

Great views from the top deck.

Turning slowly, the view shifted from water and rooftops to an endless patchwork of rice fields, stretching to the horizon in soft shades of green under the open sky.

From the upper floor, the view stretches into a patchwork of rectangular green fields, laid out with quiet precision. The plots are neatly divided by a long, straight dirt road that cuts through the landscape like a thin line drawn across fabric. From above, the fields look almost geometric, orderly blocks of color in different shades of green, some darker with thicker growth, others lighter where the plants are still young.

Standing on the rooftop and behind me is the wetland area.

From the rooftop we could go even higher by taking these stairs.

We are now at the highest point at the visitor center.

Houses below.

Inside the visitor center, the walls are made almost entirely of glass, turning the building into a quiet lookout over the wetland. Water channels, reeds, and wide green patches stretch out just beyond the windows, so close it feels like part of the room itself.

The tower is simple and understated, more about the view than what is inside, so after a short look around, we head back out, letting the landscape be the main exhibition.

From the visitor center, the path leads gently toward the wide, quiet expanse of Fukushimagata Wetland.

Long before it became a nature reserve, this area was a natural floodplain connected to the Agano River system. For centuries, seasonal rains and snowmelt from the mountains filled this low basin, creating shallow lakes, marshes, and reed beds. Local farmers depended on these waters to nourish their rice fields, and the wetland acted as a natural sponge, absorbing floods in spring and slowly releasing water during drier months.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, large parts of Niigata were reclaimed for agriculture. Many wetlands disappeared under rice paddies and drainage canals, and Fukushimagata itself was partially reduced in size. But even then, it remained one of the region’s most important habitats for migratory birds, especially swans, geese, and ducks traveling along the East Asian flyway. By the 1970s, people began to realize what was being lost. Conservation efforts started, and Fukushimagata was protected and restored as a natural wetland rather than converted entirely into farmland. Water levels were carefully managed, native plants were replanted, and human development was limited.

Today, the wetland is both a living ecosystem and a reminder of what Niigata once looked like before modern agriculture reshaped the land, a broad, breathing landscape of water, reeds, insects, birds, and slow-moving clouds reflected on its surface. Walking toward it feels less like entering a park and more like stepping back into an older rhythm of the region, where land and water still quietly negotiate with each other every day.

|

|

Scattered across the water are long, dark logs half-submerged, with grasses and small plants growing on their tops. At first they look accidental, like fallen trees left behind by a flood, but they are placed there on purpose. These are artificial floating islands and habitat logs. Park managers sink heavy logs so that only the upper portion remains above the surface. Over time, seeds carried by wind and birds take root on them, turning the wood into small living platforms. They serve several quiet but important roles for resting and nesting spots for birds, especially waterfowl and marsh birds that need safe places away from land predators. They are also natural water filters, as plants growing on the logs absorb nutrients and help improve water quality.

It was lovely to just sit down and enjoy nature.

Nearby, long narrow wooden boats tied along the wooden walkway are traditional wetland boats. Their flat bottoms allow them to glide through shallow water and dense reeds without disturbing the mud too much.

Rangers and researchers use them to monitor birds, check water plants, and maintain the wetland channels. In some seasons, they are also used for quiet eco-tours, moving slowly through the reeds so visitors can observe wildlife without breaking the stillness of the marsh.

We really enjoyed the surrounding and how peaceful this area is.

A little farther on, the path opens into a small park-like stretch. A straight walkway runs between two neat rows of tall trees, their branches forming a light green tunnel overhead. .

Sunlight filters through the leaves and breaks into soft patterns on the ground. On the right side, tall wild grass sways gently in the breeze, hiding frogs and insects that rustle as we passed through.

Continuing deeper along the outer edge of the wetland, the scenery becomes quieter and more open.

The path follows the curve of the water.

View of a little portion of the wetland as we follow the curve of the path.

This part of the wetland feels especially alive. The edges of the path are crowded with wild plants.

Seasonal flowers mixed into thick green growth. There are no sounds, only wind moving through grass and the soft splash of something slipping back into the pond.

Along the edge of the path, a soft cloud of meadow rue appeared among the taller wild plants. Their thin stems rose lightly above the grass, topped with tiny, airy blossoms that looked almost like pale mist floating in the green. Compared to the bold colors of other flowers nearby, these were delicate and subtle, easy to miss unless you slowed down.

Across the pond the visitor center appears in the distance. From here it looks small and far away, almost floating above the reeds.

We are now done with the visit and we are walking back to the visitor center.

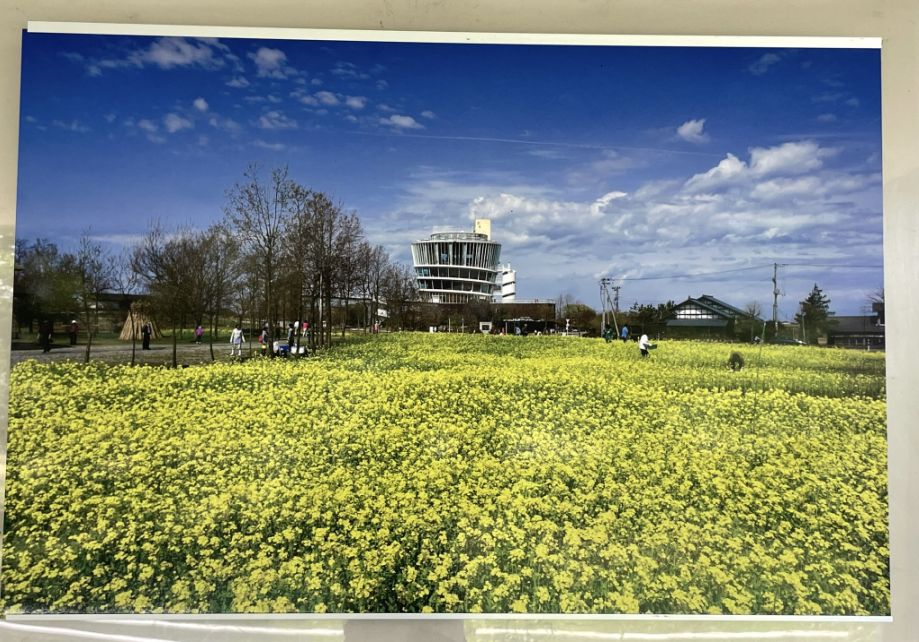

On the fence near the path back to the visitor center, several photographs were displayed, quietly telling the story of the wetland through the seasons. One showed the visitor center in the distance, surrounded by a wide field of bright yellow flowers.

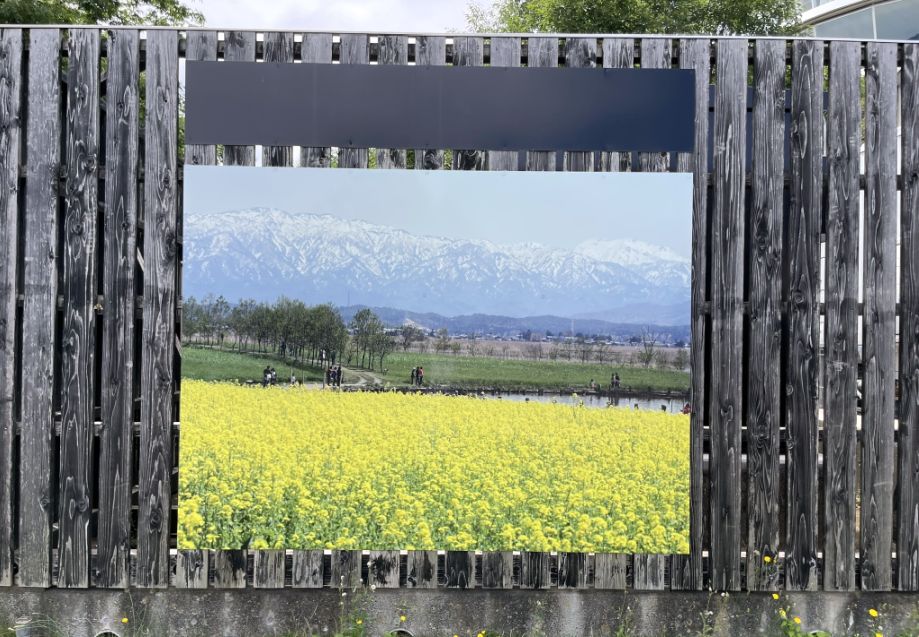

Another captured the same golden field stretching toward the wetland, with mountains rising behind it, their summits still capped with snow.

A third photo showed children walking beside tall lotus plants in summer, pink blossoms floating above the water and mirrored perfectly in their reflections.

The last image was taken in winter, when the entire wetland lay silent and white under a blanket of snow, the landscape transformed into something calm and endless.

Our visit to Fukushimagata felt like stepping into a quiet, hidden side of Japan that few travelers ever see. Surrounded by endless rice fields, wetlands, rivers, and small farming villages, everything moved at a slower, gentler pace. There were no crowds, no tour buses, and no noise, just wind in the grass, still water under the bridges, and the rhythm of rural life unfolding naturally around us. Walking along narrow paths between flooded rice fields, watching wildflowers bloom beside canals, and seeing farmers’ crops stretch to the horizon made the experience deeply special. It felt honest and untouched, a kind of everyday Japan that doesn’t appear in guidebooks, and one we will remember long after the trip ended.

NEXT... Day 5- walking around Niigata