9 days in Japan- 6/23- 7/1/2024

Day 4-Northern Culture Museum, Niigata-6/26/2024

This museum is the former residence of the Ito clan, major landowners in the region. Construction started in 1882 and took eight years to complete. Built in traditional Japanese style, the 42,700 sq. ft. home has 65 rooms , and the size of the property is 7.2 acres. Perhaps most interesting is the large (100-mat) reception hall, used only for family ceremonies, with its beautiful view of the grounds.

|

|

This morning we headed out from our hotel toward Northern Culture Museum, a historic estate and cultural site that gives a fascinating glimpse into Niigata’s past.

We first took the Joetsu Shinkansen train, once we got off the train, we walked about 5 minutes to the Bandai City Bus Center, then a 40-minute bus ride toward Akiha Ward via the Somi area. The bus let us off in the middle of farm land.

We are now at the entrance of the Northern Culture museum that is housed in the former residence of the Ito family, once among the wealthiest landowners in Niigata. The mansion was built in the Meiji era (late 19th century) and took many years to complete, resulting in a sprawling estate with 65 rooms spread over nearly 30,000 square meters of grounds.

Northern Culture Museum sign next to the entrance.

|

|

We entered the museum grounds through the main gate and found ourselves on a long, quiet walkway lined with beautiful trees and neatly trimmed bushes. The path felt calm and almost ceremonial, gently guiding us away from the modern world and into another time.

At the end of the walkway stood a simple building that marked the entrance to the estate.

|

|

Unlike the grand homes beyond it, this entrance was modest and understated, with a wooden gate and a small sign to the side indicating where to buy tickets. There was nothing flashy about it, just a quiet confidence, as if the place did not need to announce its importance.

We are now walking inside the compound.

Once inside, we continued forward, passing along a fenced area that hinted at the size of the grounds beyond. Through the gaps, we could glimpse more trees, traditional buildings, and carefully kept gardens waiting to be explored, giving us our first sense of how large and peaceful the estate truly was.

We followed a quiet walkway lined with traditional wooden houses, their dark beams framed by tall trees and carefully shaped bushes. Everything felt balanced and deliberate, as if the landscape itself had been composed.

In the middle of one garden stood a large stone monument.

As we came closer, we noticed two sculpted portraits, head-and-shoulder reliefs of two men set into the stone, with a black plaque beneath them covered in Japanese writing. These are indeed connected to the estate’s history: they commemorate members of the Ito family, the wealthy landowners who built and lived on this property for generations. The monument honors their role in developing the estate and their influence in Niigata’s agricultural and cultural life.

|

|

Continuing on, we passed elegant stone lanterns placed beside the path. They added a quiet, timeless feeling, guiding the way just as they would have done for guests more than a century ago.

As we moved forward we discovered a Gazebo on the left.

The gazebo was covered completely in a living roof of vines. The plant is actually wisteria, not green beans, though the long hanging seed pods can look similar from a distance. In spring, this structure becomes famous for its cascading purple flowers, but even without blooms, the thick green canopy felt cool and peaceful.

Inside the gazebo was a small pond and a few simple benches, a place clearly meant for resting and quiet reflection.

Sitting there, surrounded by water, leaves, and silence, it was easy to imagine the original owners pausing in the same spot, listening to the wind in the trees, far removed from the world beyond the gates.

A little farther on, we came to a small shop with a row of wooden benches out front. We sat there for a while, saying nothing, just enjoying how quiet everything felt, as if time had slowed to match the rhythm of the garden.

The building was simple, with clean lines and natural wood, very typical of traditional Japanese architecture.

Nearby was the farm house and the famous lotus pond. We are heading to the lotus pond first.

I am reading the story of the ancient lotuses plants.

This pond is known for its ancient lotus plants, descendants of seeds that are said to be hundreds or even over a thousand years old, carefully preserved and cultivated here.

Its surface stretched wide and calm, dotted with large round leaves floating like green plates. In summer, pale pink flowers rise above the water, but even without blooms, the scene felt gentle and timeless, the broad leaves overlapping and catching the light. In the summer, pale pink flowers rise above the water, but even without blooms, the scene felt gentle and timeless, the broad leaves overlapping and catching the light.

We crossed the pond on a narrow wooden walkway, the water just below our feet, moving slowly between the stems and shadows.

Crossing to the other side of the pond.

From the middle of the bridge, the estate looked especially serene, framed by trees, old buildings, and still water.

After the pond we followed a path leading to an old house.

|

|

A small stream flowed quietly between stones and water plants.

|

|

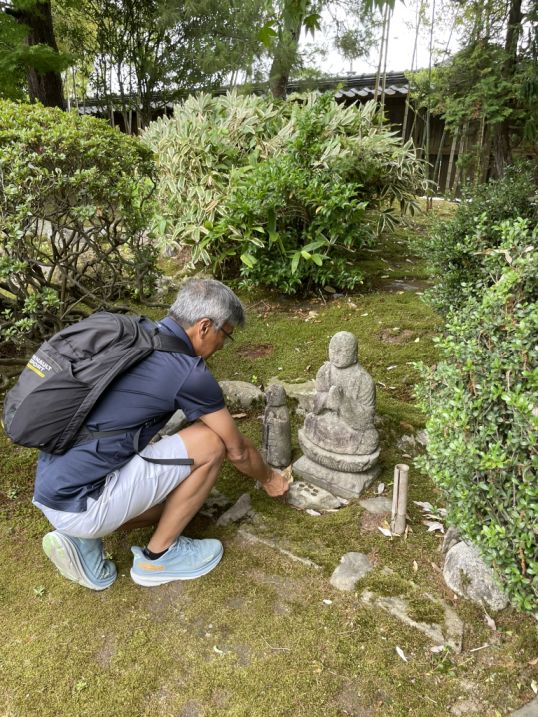

On one side stood a simple cement Buddha statue, weathered and calm, with a smaller statue beside it. Hoa knelt down and placed a coin near the Buddha’s feet, joining the many others already resting there, a quiet gesture of respect in a place that invited silence more than words.

From there we entered Yoshigahira House, an old Japanese house that was built early in the 19th century in the mountains village of Yoshigahira in the town of Sanjo in Niigata Prefecture from where it was brought down and rebuilt here. It has several features typical of snow regions such as curved timbers and a wing jutting out in front with a passage to the main house.

The first room felt like stepping into another century. What looked like an old kitchen spread out before us, with several raised traditional stoves built from clay and stone. Each had a round opening at the top for a pot, and space below where charcoal or wood would once have burned. Around them stood wooden barrels, baskets, ladles, and every kind of kitchen tool imaginable, darkened by age and smoke.

The floor was bare, packed earth, cracked in thin lines from decades of footsteps and seasons passing.

We then walked into the main room, where the heart of the house awaited: a square wooden frame set into the floor, with a sunken center covered by a metal grill. Above it hung an iron kettle, suspended from a hook on a wooden beam. This called an irori, the traditional Japanese hearth.

Standing there, looking at the kettle hanging over the quiet ashes, it was easy to imagine evenings filled with firelight, steam, and soft conversation. The house no longer held people, yet it still carried their warmth, as if it had settled into the walls and floors and decided to stay.

|

|

It served many purposes at once. It was used for cooking, for boiling water, and for heating the room during cold Niigata winters. Families would gather around it to eat, talk, and work, the rising smoke slowly drifting up into the ceiling, helping to preserve the wooden beams from insects while darkening them to the deep color they still hold today.

View of the garden from inside the house.

We then walked past a traditional farmhouse. Outside, many pieces of old wood cart wheel were stacked neatly along the wall, likely parts of carts and carriages once used to transport rice and supplies across the estate.

The house itself had a thick straw-thatched roof, layered and heavy, designed to keep the interior warm in winter and cool in summer.

From this spot, the lotus pond was still visible in the distance, its broad green leaves floating quietly on the surface.

|

|

A little farther on, we passed through a wooden gate with a small roof, marking the entrance to another section of the grounds.

Inside was a cluster of traditional buildings arranged around gardens and stone paths. On the left is the Sanrakutei Tea House that was build in 1891 as a study and tea house.

The room are triangular or diamond-shaped and apart from the center mat, the tatami is also triangular or diamond shaped. Such a Tea house is unique to Japan

The tea house is set beside a carefully designed garden filled with moss, trees, and stone lanterns placed at thoughtful intervals.

From there, we walked toward the main house, a large two-story residence that once served as the heart of the Ito family estate.

Stairs going to the 2nd floor.

On the second floor, we stepped into a long, quiet gallery corridor with smooth wooden floors that creaked softly underfoot. Along the left wall, a continuous row of glass cabinets displayed delicate vases, ceramics, and small historical objects, arranged carefully as if in a private family collection rather than a museum.

The light filtering in from the windows reflected faintly on the glass, giving everything a hushed, reverent feeling.

|

|

Further along the corridor stood something unexpected: the fragile frame of an ancient boat, lifted on wooden supports. Only the ribs of the vessel remained, curved like the skeleton of a long fish. A small sign explained that it was a dugout canoe, excavated in 1951 and estimated to be about 1,000 years old. Once carved from a single massive tree trunk, it would have been used on nearby rivers and wetlands long before modern Niigata existed. Seeing it inside this refined residence created a striking contrast between everyday ancient life and the later wealth of the estate.

Rooftops view from the second floor,

Portrait of the Ito family, the largest landowners in the Echigo region

The history of the house itself is closely tied to the man who preserved it: Ito Bunemon VIII, the last head of the Ito family to live here.

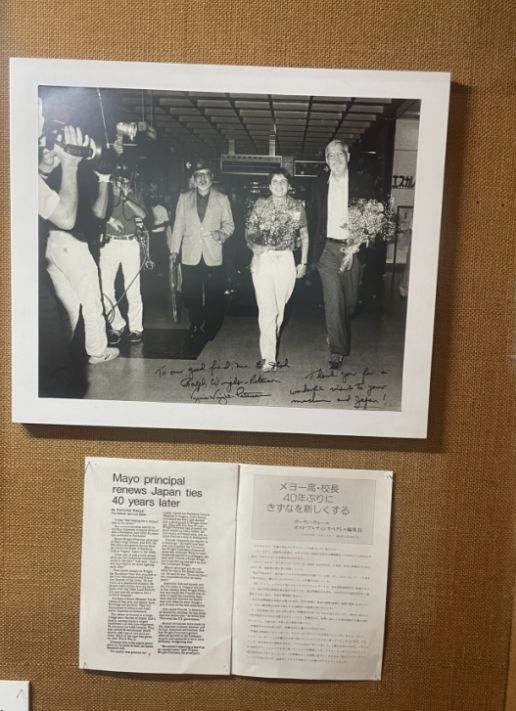

In the mid-20th century, he became friends with a Ralph Wright, a scholar who was deeply interested in Japanese rural culture and architecture. Through many conversations, this friend urged him not to let the estate disappear or be broken apart after the war, but instead to protect it and share it with the public. Moved by this idea, Ito Bunemon decided to open the property as what later became the Northern Culture Museum, allowing visitors to experience the life of a wealthy Niigata landowning family and the traditions of the region.

|

|

Wright was an American Civil

Education Officer during the post-war occupation.

After the war, Wright returned to the United States (settling in Minnesota and becoming a high school principal), and the two families lost touch. Ito VIII spent over 30 years searching for Wright to thank him for saving the family estate. He eventually tracked him down, and the reunion took place in 1985, roughly 40 years after their initial meeting in 1945/1946.

We are now back on the first floor, stepping into the largest room of the house.

The room is a vast open space covered wall to wall with 100 tatami mats. The straw scent was faint but still present, and the soft surface made every footstep quiet and deliberate. Along the far edge of the room ran a narrow red carpet border, a subtle line of color that marked where important guests once sat.

This was the family’s main reception hall, used for formal gatherings, seasonal ceremonies, business meetings with merchants and officials, and special celebrations. For a landowning family as powerful as the Ito clan, this space was meant to impress, not through luxury, but through scale, harmony, and restraint.

One entire side of the room opened toward the garden through wide sliding doors. From inside, the view felt like a living painting: trimmed pines, stone lanterns, and mossy ground arranged with careful balance. When filled with people, the room would have been divided by sliding screens into smaller sections. Low tables would be set out, meals served, and important conversations held while servants moved silently along the edges.

Standing there now, in the quiet, the emptiness made the room feel even larger. It was easy to imagine silk kimono brushing across the tatami, the soft clink of cups, and the murmur of voices drifting out toward the garden. Even without furniture, the space still carried the weight of formality and the elegance of a life once carefully choreographed within its walls.

The room and garden were designed as one composition, with the interior acting as a calm frame for the landscape outside.

After leaving the museum grounds, we walked down toward a quiet cemetery and small shrine tucked near the edge of the estate. These places are often found together in Japan: the cemetery honoring ancestors, and the shrine offering a place to pray for blessings, safety, and peace

We followed the street to the shrine.

The small Shinto shrine, unmistakable by its torii gate and simple wooden structure. Shrines like this are often part of everyday life in Japanese communities, places to pause, reflect, and give thanks.

Shinto shrines are closely linked to the rhythms of life in Japan. Even when modest in size, they carry centuries-old traditions of reverence for nature, ancestors, and daily blessings. Walking slowly through this area, the quiet of the cemetery and the gentle design of the shrine felt like a natural extension of what we’d seen inside the museum, layer of the cultural and spiritual world that surrounded the lives of families like the Ito clan.

At historic properties in Japan, it’s very common to find family graves and small shrines.

We are now leaving the area and heading to the Ito family cemetery.

At the entrance to the cemetery stood a simple but solemn wooden gate, darker than the surrounding buildings, its roof slightly curved and softened by age. It did not feel grand or decorative, but purposeful, marking a quiet boundary between the everyday world and a space meant for remembrance. Passing through it felt like lowering one’s voice instinctively, as if the gate itself asked for calm and respect.

The cemetery was simple and respectful, rows of stone markers shaded by trees, each with polished surfaces and small offerings left at their bases. These kinds of family cemeteries are common near historic estates because in traditional Japanese culture, families often maintained their own burial plots close to home or near temples connected to their lineage. People place fresh flowers, incense sticks, and small offerings at the stones out of respect for ancestors and family history.

In this quiet setting, it felt like a continuation of everything we had just seen inside the museum: not just buildings and gardens, but the lives and memories of real families who shaped the place.

Just beyond the gate was a small traditional Japanese building, modest in size, with sliding doors and deep eaves. This structure serves as a cemetery hall, a place where families can rest briefly, prepare offerings, shelter from rain or snow, and sometimes hold small memorial services. Inside, people may light incense, arrange flowers, or say prayers before visiting individual graves.

In the garden stood a wooden bell tower sheltering a large bronze temple bell, its surface now a soft green from centuries of oxidation. This color, called verdigris, forms naturally as copper in the bronze reacts with air and rain over time, creating a protective layer that gives old bells their quiet, jade-like tone.

Bells like this are known as bonshō and have been used in Japan for more than a thousand years. Unlike church bells, they are not rung with a swinging clapper. Instead, they are traditionally struck from the outside with a suspended wooden log, producing a deep, lingering sound that can travel for miles.

|

|

The bell would have been used to mark time, announce important moments, and most of all to accompany prayer and remembrance. In Buddhist tradition, each toll is believed to cleanse worldly worries and remind listeners of the passing nature of life. Standing there in silence, it was easy to imagine the low, resonant note rolling across the gardens and fields, fading slowly into the trees and sky.

We are now done with our visit and we are now walking back to the bus station.

NEXT... Day 4- Farm Land