9 days in Japan- 6/23- 7/1/2024

Day 3-Hakusan Shrine, Niigata-6/25/2024

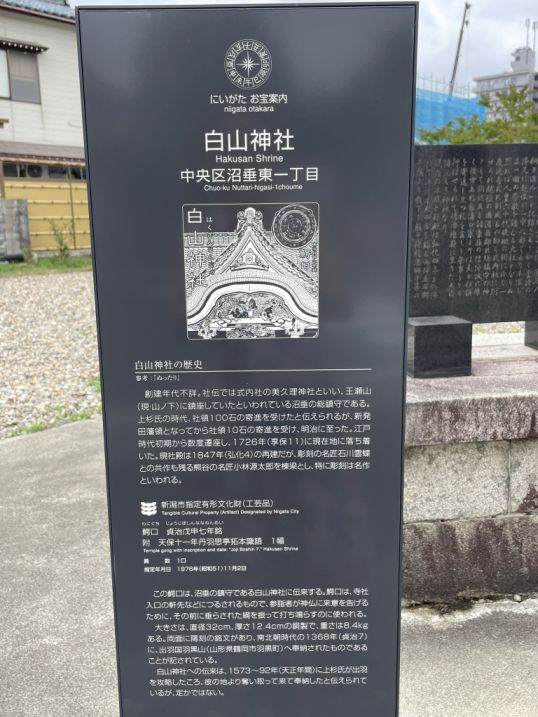

This morning we are headed to Hakusan Shrine, one of the city’s oldest and most important Shinto sites.

Hakusan shrine has a history stretching back over a thousand years and is known locally as the “guardian shrine” of Niigata, deeply connected to the community and the region’s history.

Hakusan Shrine is dedicated to Kukurihime-no-kami, a goddess traditionally associated with harmony, good relationships, and protection over home and family life. People visit not only for spiritual blessings like successful business, safe travel, family well-being, and marriage, but also for traditional events such as hatsumōde (New Year’s prayers), shichigosan, and seasonal festivals that draw local worshippers.

The shrine gates and tranquil precincts are set beside Hakusan Park, a long-loved green space in the city that blooms in spring and offers peaceful places to walk and reflect. It’s a pleasant mix of quiet nature and cultural tradition right in central Niigata.

As you approach Hakusan Shrine, the experience unfolds in layers, marked by two main gates that gently transition you from the city into a sacred space.

|

|

The first gate is a torii, the classic Shinto shrine gate. Simple in structure but powerful in meaning, it signals that you are leaving the ordinary world and entering a place where the gods are believed to reside.

|

|

Standing on either side of this gate are the two stone guardian lions, called komainu.

One has its mouth open, forming the sound “A”, the first letter of the Sanskrit alphabet. The other has its mouth closed, forming “Un”, the last letter. Together, they symbolize the beginning and the end of all things, much like “alpha and omega.” Their role is to ward off evil spirits, protect the shrine, and guard the boundary between the human world and the sacred realm.

Farther in, you reach the second gate, which feels more intimate and ceremonial. By this point the sounds of traffic have faded.

|

|

This gate marks your true arrival into the shrine’s inner grounds, where visitors slow down naturally, bow lightly, and prepare to approach the main hall.

Together, these two gates create a gentle progression : city-sacred boundary-quiet spiritual center.

It is not dramatic or grand in the way of famous shrines in Kyoto, but calm, grounded, and deeply connected to everyday life in Niigata.

Beyond the second gate, the path opens into a quiet courtyard where the main worship hall (haiden) stands. The building is elegant but understated, made of dark wood with a gently curved roof, blending naturally into the surrounding trees. Nothing feels overly ornate. Instead, there is a calm simplicity that suits Niigata’s quiet character.

|

|

Before approaching the hall, visitors usually stop at the temizuya, the stone water pavilion to rinse both hands, pour a little water into the left hand to rinse the mouth. It is not just about cleanliness, but about leaving the outside world behind and approaching the shrine with a clear mind.

At the front of the hall hangs a thick rope attached with thick decorative tassels, bundles of tightly woven threads hanging down in front of the offering area. They swayed slightly in the air, soft and heavy, more ceremonial than functional. In some shrines these replace the bell rope, serving as a visual focus for prayer rather than something to be rung.

As we moved closer, the space became more formal and protected. Directly ahead stood a wooden inner gate, simple but solid, its dark beams aged smooth by time. The gate itself was closed off with a wooden lattice, allowing us to see inside but not enter.

Through this trellis, we could glimpse the inner prayer hall, quiet and decorated with sacred objects deeper within. It felt intentionally distant, reserved for priests and rituals, while visitors remain outside to pray.

Standing there, looking through the wooden lattice into the stillness beyond, the shrine felt both welcoming and private at the same time. It wasn’t grand or dramatic, but quiet and deeply respectful, as if the most important part was meant to be sensed rather than seen.

|

|

We are now leaving the main hall and looking at the courtyard.

As we wandered deeper into the grounds, one area immediately caught our attention. A few dozens of small wooden plaques, called Ema, were hanging neatly together, each covered in handwritten Japanese characters.

|

|

Visitors buy them at the shrine and write their wishes or prayers on the back, health for family, success in school, safe travels, love, or simply happiness. They hang them here, believing the gods will read their words. Standing close, you can feel how personal the space is: countless quiet hopes layered together in wood and ink, gently tapping against one another in the breeze.

This is the side of the Shrine with a statue of a Monk carved directly into a large natural rock.

|

|

The figure looked calm and timeless, its features softened by age and weather. Underneath was a dark, square plaque with Japanese writing, likely explaining who the monk was or commemorating a historical religious figure connected to the area. This statue reflects the quiet blending of Buddhism and Shinto that exists all over Japan. Even within a Shinto shrine, traces of Buddhist history remain, monks, memorial stones, and small sacred markers woven gently into the landscape.

|

|

Along the side of the main shrine, near the fence, we noticed a much smaller shrine tucked slightly away from the main path. These little shrines are dedicated to secondary or local deities, spirits connected to specific needs such as protection, business success, fertility, or safe journeys. They are humble in size but often deeply meaningful to locals who return again and again to pray to a particular god.

![]()

Otoko shrine

As we walked around the Hakusan Shrine grounds, we unexpectedly came across a smaller shrine tucked nearby called Otoko Shrine. It’s easy to miss if you’re not looking closely, but the peaceful atmosphere around it makes it worth stopping for a moment.

Otoko Shrine literally means “male shrine,” and in this context the name refers to a mythological connection with the youngest child of important deities in Shinto mythology, including Amaterasu Ōmikami, the sun goddess revered across Japan. The shrine is thought to enshrine Ken Morozumi (also known as Mononobe Takesumi) and Ame-no-ho, figures tied to ancient Japanese myth and genealogy, and it is said to have traditionally been part of the larger Hakusan Shrine precinct.

The structure itself is much smaller and quieter than the main Hakusan Shrine buildings, but that’s part of its charm. Stepping up to it feels like discovering a hidden corner of worship. a space that feels intimate and local rather than grand or touristy. People still leave their prayers and offerings here, and the air around it feels calm, sheltered by trees and a sense of history.

Because Otoko Shrine was originally connected to Hakusan Shrine’s precincts, it acts like a subsidiary or companion shrine, one of the smaller spiritual sites that many larger shrines keep on their grounds or immediately beside them. These smaller shrines often honor specific kami (Shinto deities) or mythological figures with particular roles, such as protection, family blessings, or ancestral reverence.

The two lion guardians in front of the main gate.

|

|

Ema hanging in a much smaller wooden structure. It’s a lovely little discovery and a reminder that even within a single shrine complex, Japan’s spiritual landscape can have many layers, stories, and quiet places to pause.

We were a bit surprised to find out that there are not a lot of temples in Niigata and we found out why. While Kyoto and Nara were political and religious centers for centuries. Emperors, powerful clans, and Buddhist schools built large temples there to display wealth, influence, and devotion. Over time, thousands of temples accumulated. Niigata, on the other hand, grew mainly as a port city, a center for rice farming and trade, a practical working city rather than a religious capital. Its importance came from commerce and transportation along the Sea of Japan, not from being a seat of emperors or major Buddhist institutions. Niigata’s communities traditionally relied more on local Shinto shrines for everyday life events, harvest prayers, fishing safety, health, and family milestones, rather than large Buddhist centers. During WWII parts of the city were damaged and later rebuilt with modern buildings. Unlike Kyoto, Niigata did not preserve large temple districts as cultural treasures. Hakusan Shrine stands out so clearly because it is the city’s most important Shinto shrine, founded over a thousand years ago, and dedicated to the deity of Mount Hakusan, a sacred mountain associated with protection, water, and agriculture, perfectly suited to a region shaped by rivers, rice fields, and the sea.

NEXT...Day 3-Sake Brewery tour