6 days in Tasmania, Australia- 5/11- 5/16/2024

5 day tour of Tasmania

Cradle Mountain, Lake St. Clair National Park-5/12/2024

Afterward Russell Falls, Tom, our tour guide drove about 2 hours to reach Lake St. Clair, a place of serene beauty and deep wilderness. Known as Australia’s deepest natural freshwater lake, it was carved by glaciers during the last Ice Age and sits surrounded by rugged mountains and dense forest. The water is calm and crystal clear, reflecting the sky and distant peaks like a mirror. The area feels incredibly peaceful, with only the sound of wind through the trees and the occasional call of birds echoing across the lake. It’s easy to see why Lake St. Clair is considered one of Tasmania’s most tranquil and awe-inspiring natural landscapes.

|

|

From the parking lot, we followed a short trail leading down to the shore of Lake St. Clair. The Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair area was declared a scenic reserve in 1922, a wildlife reserve in 1927, a national park in 1947 and a world heritage area from 1982.

The path was lined with tall trees, and as we walked, glimpses of the shimmering lake began to appear through the branches.

Before reaching the shore, we came across a wooden deck that offered a beautiful first glimpse of Lake St. Clair.

From there, the view suddenly opened up, the calm, glassy surface of the lake stretched out before us, surrounded by forested hills and distant peaks. The sunlight shimmered on the water, making the whole scene feel peaceful and expansive.

On the sandy beach, a large twisted tree trunk caught my attention. Its gnarled shape looked sculpted by years of wind and water, bleached smooth by the sun. Lying against the pale sand with the lake in the background, it added a wild, natural beauty to the quiet shoreline, like a piece of art created by nature itself.

We sat down by the shore to take in the beautiful view of the calm lake. The water was perfectly still, everything felt peaceful. It was a quiet, soothing moment surrounded by pure Tasmanian wilderness.

I noticed that the beach was quite rocky, with smooth stones scattered across the sand and along the shoreline. The mix of rocks and sand gave the shore a rugged, natural look that matched perfectly with the stillness of the lake and the wild beauty all around.

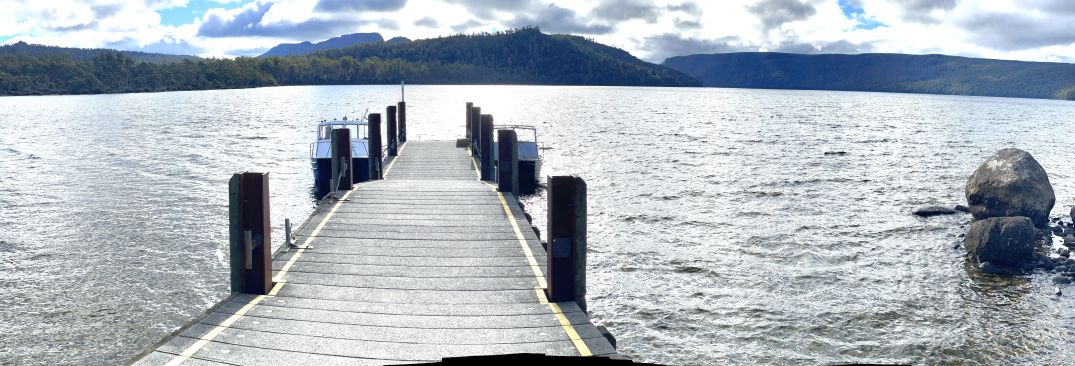

Panoramic view of the shore.

A long tree trunk stretched along the shore, perfectly positioned to serve as a natural bench where we could sit and admire the lake.

Further down the rocky beach, a few more fallen trees lay scattered, their trunks dried and weathered by the sun. Their pale, twisted shapes stood out against the dark stones and clear water, adding to the raw, untouched beauty of the lakeside.

From the beach I can see Cynthia bay with the wharf extending over the calm water. We are heading over there but there is not access from where we stood on the beach.

We passed by the visitor center to reach the wharf.

The wharf extends gently over the clear water and is used for boat tours, fishing, and sometimes for hikers starting or finishing the famous Overland Track, which ends here. As we were approaching the wharf, a bunch of people just got of the boat after hiking on the other side of the lake.

The wharf and calm blue water create a picture-perfect scene that captures the quiet beauty of Tasmania’s wilderness.

Standing on the wharf, I looked out across Lake St. Clair and saw mountains rising all around the water, their slopes covered in dense forest.

The lake stretched out wide, and everything felt calm and untouched, as if the entire landscape had been perfectly preserved in time. It was a breathtaking view and so peaceful.

View from the end of the wharf to the shore of the lake.

The white sandy beach you see toward the end is where we where when we arrived at the Lake St. Clair.

Large rocks on the shore of the lake.

We are now headed to the parking lot and on to our next destination.

![]()

Franklin–Gordon Wild Rivers National Park

|

|

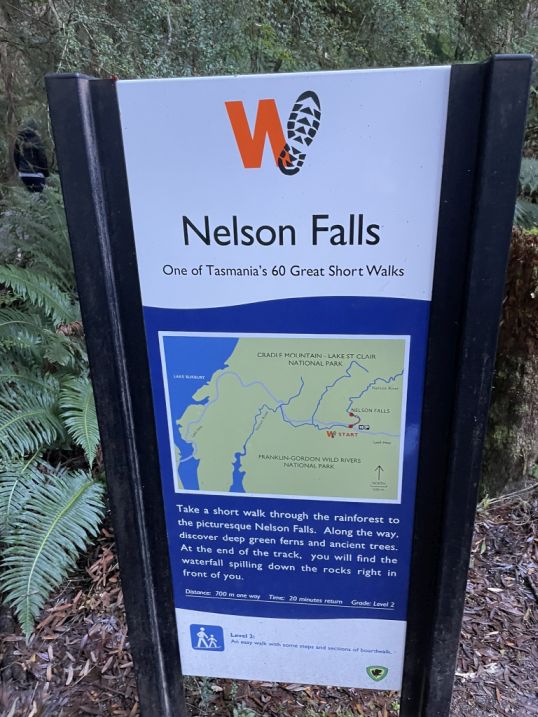

After an hour of drive we have reached Nelson Falls track located within the Franklin–Gordon Wild Rivers National Park, which is part of Tasmania’s World Heritage Wilderness Area. This park is one of the most pristine regions in the world, protecting ancient rainforests, glacial valleys, and wild rivers that have been flowing for millions of years. The Nelson Falls Track is a short, easy walk through lush temperate rainforest, where moss-covered trees, ferns, and trickling streams line the path. The falls themselves are named after the nearby Nelson River, and they cascade beautifully over a tiered rock face into a clear pool below, a perfect example of Tasmania’s untouched natural beauty.

We are now starting Nelson Falls Track, a short and scenic walk that is about .8 mile that winds through the lush temperate rainforest of the Franklin–Gordon Wild Rivers National Park.

As we walked along the Nelson Falls Track, we followed a stream winding gently through the forest, its clear water glimmering between rocks and roots.

The trees surrounding it were thickly covered in moss, gave the trunks a vivid green color, and together with the towering height of the trees, it created the feeling of an enchanted forest. All around, large boulders blanketed in moss added to the sense of ancient stillness, as if the forest had been untouched for centuries.

Mossy boulders, fallen logs, and the sound of water running through the stream is very peaceful.

Wooden bridge where the stream flowed gently right beside us. This is a good place to take a picture of the surrounding.

As we followed the well-kept wooden pathway toward Nelson Falls, we are now walking through a cool temperate rainforest filled with a mix of ancient Tasmanian tree species.

The dominant trees here are myrtle beech (Nothofagus cunninghamii), which have dark, glossy leaves and form much of the dense canopy. There are also sassafras, which gives off a faint, sweet scent when crushed, and leatherwood trees, known for their twisted trunks and creamy white flowers in summer.

We came to another wooden bridge, suspended over the flowing stream.

In some areas, tall eucalypts like Stringybark or swamp gums rise above the rainforest, while the understory is thick with tree ferns, moss, and lichens. Together, these create the lush, green world that makes the Nelson Falls Track feel so ancient and alive.

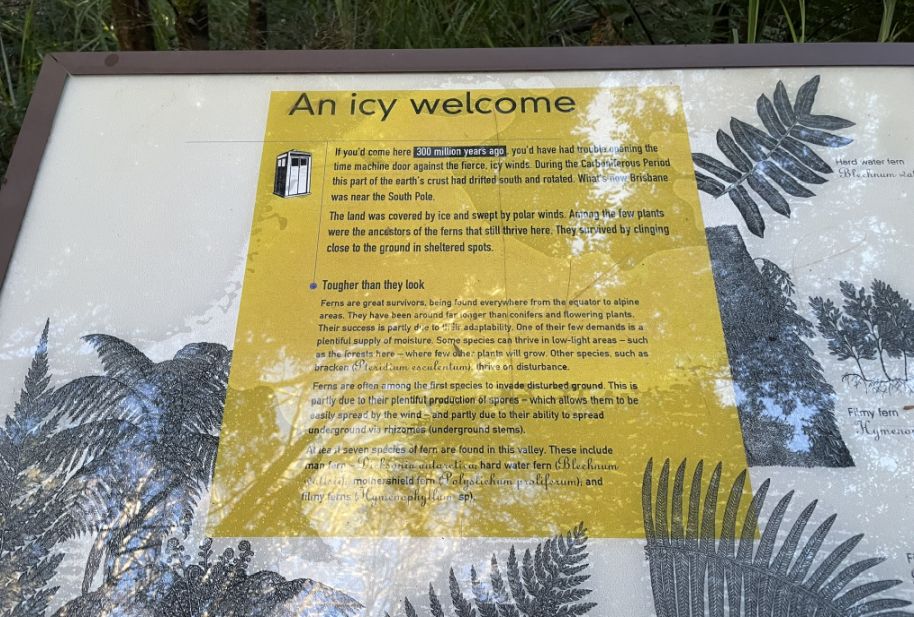

A panel titled “An Icy Welcome”, explained how this entire landscape was shaped by glaciers during the last Ice Age, when massive sheets of ice carved out valleys and left behind the rivers and waterfalls we see today. The sign helped put the scenery into perspective, reminding us that the moss-covered rocks, flowing streams, and deep valleys around Nelson Falls are part of a landscape millions of years in the making, sculpted slowly by ice and time.

In this section, ferns grew in abundance, their wide green fronds stretching out toward the walkway. Some were small and delicate, while others stood tall, almost as high as our shoulders. They filled the spaces between the moss-covered trees, creating a soft, layered texture of greens.

As we walked further, I noticed the sunlight trying to break through the trees, its golden rays filtering softly through the thick canopy.

The shining beams of light made parts of the forest glow in shades of green and gold. It was a beautiful contrast, the warm light mixing with the cool, shaded air, making the whole scene feel alive, as if the forest were gently waking up under the touch of the sun.

The pathway wound its way through tall myrtle beech trees, their trunks thickly covered in moss from base to branch. These ancient trees are characteristic of Tasmania’s cool temperate rainforests, thriving in the damp, shaded environment around Nelson Falls. Some sassafras and leatherwood trees also grow among them, adding variety to the dense forest canopy.

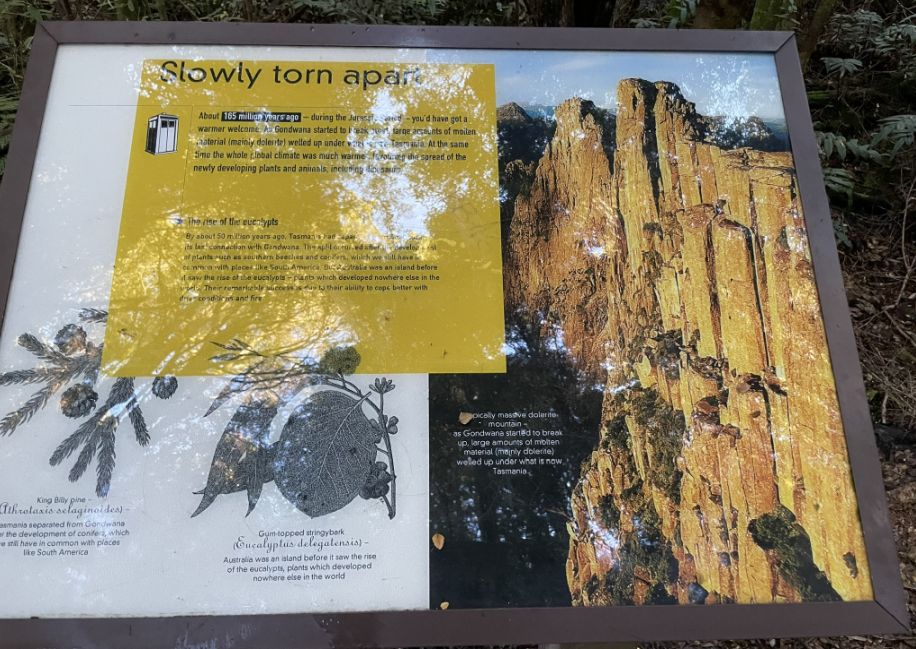

A little farther along, we came across another interpretive panel titled “Slowly Torn Apart.” It described how over millions of years, the landscape around Nelson Falls has been shaped by powerful natural forces by glaciers carving deep valleys, and later by the constant flow of water and erosion. The panel explained how the rocks and cliffs we see today are still slowly being worn down by rain, wind, and the steady movement of the river. It was fascinating to realize that even in such a peaceful, timeless place, the land is still quietly changing.

|

|

I noticed that the trees along the track have relatively slender trunks, yet they grow remarkably tall, reaching high into the canopy. Their height makes them seem even more graceful, stretching upward to catch the filtered sunlight that seeps through the dense forest. Covered in moss and surrounded by ferns, these tall, narrow trees give the rainforest a sense of quiet elegance and depth, as if every tree is reaching for the light in its own steady way.

Myrtle Beech trees can grow 164 ft. tall and surviving for over 500 years, giving the forest its powerful, timeless feel. You definitely feel so small walking among them.

Continuing our trek...

We got deeper and deeper into the forest.

|

|

As we followed the trail surrounded by tall, lush ferns, the sound of rushing water grew louder with each step.

The air felt cooler and mistier, and soon the forest opened up to reveal Nelson Falls cascading down a rocky cliff. The water flowed in delicate white streams over moss-covered rocks, spreading out like a fan before pooling below. It was a breathtaking sight with the waterfall framed by greenery, its steady roar echoing through the peaceful rainforest.

|

|

Unlike a plunge waterfall, the water here doesn't drop in one clean

sheet. It descends in a long, wide cascade,

meaning it tumbles, slides, and bounces down a series of stepped, terraced

rock faces.

The water pours over rough, dark, and often

tiered black rocks.

The constant mist keeps the surrounding rocks and ferns vibrant green, adding to the sense of freshness and life. What makes Nelson Falls especially striking is its setting, the falls are framed by dense rainforest, where every surface seems alive with moss, lichen, and ferns. Standing in front of it, you can feel the cool spray and hear the deep, rhythmic sound of the water.

Dense forest all around the Falls.

We are now leaving the Falls and getting back to the bus.

![]()

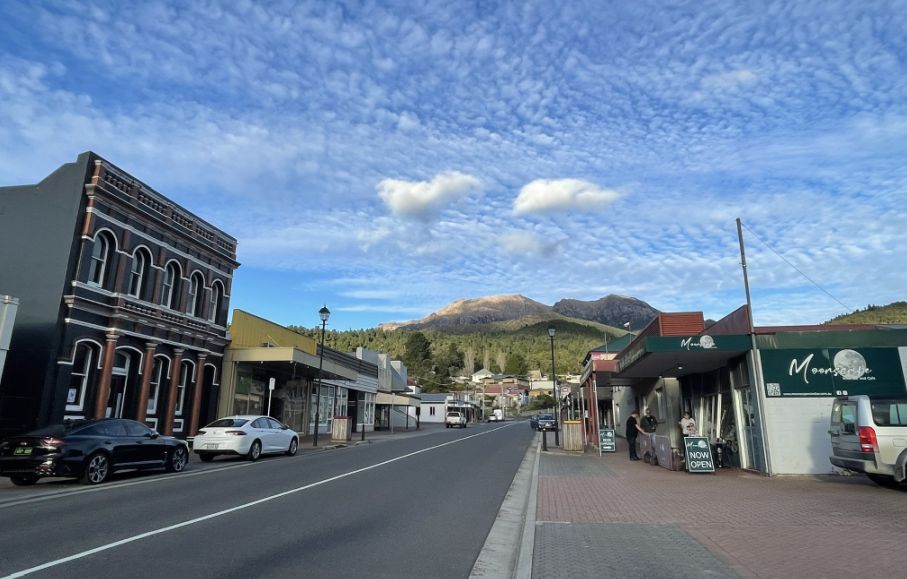

Queenstown

After a 30 minutes bus drive we arrived in Queenstown, located on Tasmania’s rugged west coast, and has a fascinating and dramatic history shaped by mining. The town was founded in the late 19th century after rich deposits of copper, gold, and silver were discovered in the surrounding mountains. It quickly became one of the most important mining towns in Australia, especially after the establishment of the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company in 1893. During its mining boom, Queenstown thrived, but the intensive mining and smelting (process of extracting metal from its ore by heating it a high temperature) which left a lasting mark on the landscape. The surrounding hills were stripped of vegetation, and years of acid rain from smelter fumes created the town’s now-famous “moonscape” hills, bare, rocky slopes with rich red and orange hues.

Today, Queenstown has transformed from an industrial center into a place known for its heritage, art, and wilderness access. Visitors come to see its unique scenery, ride the West Coast Wilderness Railway, and explore its mining history, all set against the dramatic backdrop of Tasmania’s wild west coast.

Walking along Queenstown’s main street, you can’t help but notice how the town sits in a deep valley, surrounded by rugged mountains.

The Queenstown Post Office is one of the town’s most recognizable and historic buildings, standing proudly along Orr Street, the main street of Queenstown. Built in the early 1900s, during the height of the mining boom, the post office served as a vital communication hub for miners, businesses, and families when Queenstown was a bustling industrial center.

Architecturally, the building reflects Federation-era design, with its arched windows, decorative brickwork, and clock tower that once helped residents keep time in a town defined by long work hours and shifting mine schedules. The warm, earthy tones of its stone and brick façade blend beautifully with the surrounding mountains, giving it a timeless, sturdy character. Today, the Queenstown Post Office still stands as a reminder of the town’s prosperous past, and a symbol of how this remote mining settlement once connected Tasmania’s wild west coast to the rest of the world.

The town’s main street is Orr Street, which is often referred to as the “main street”, with many of the key shops, services, and heritage buildings, and it’s the commercial heart of Queenstown.

The big general store you see in Queenstown is a reminder of the town’s mining boom days. During the early 1900s, when Queenstown was one of Tasmania’s busiest mining centers, general stores like this were vital in supplying everything from food and clothing to mining gear for workers and their families. Many of these stores were built with solid brick or timber facades and large front windows, giving them a sturdy, practical look that still fits the rugged character of the town today. Even now, the general store continues to serve as a central hub for locals and traveler, a place to grab supplies, exchange news, and get a sense of everyday life in this remote mountain community

Old buildings, many of them historic, line the quiet street with an old-fashioned charm that reflects the town’s mining past.

Hunters Hotel was built around 1898 and is a heritage-listed building on Orr Street, right in the middle of Queenstown’s main street. The hotel has played an important role in the town’s community life. Its balcony was used as a platform for speeches by political figures, including King O’Malley (a prominent early-20th-century politician), especially for miners and town meetings. In 1912, after the North Lyell mine fire (where 42 men died), the hotel balcony was used to keep the distressed community updated on what was happening.

Hunters Hotel had been closed for about 20 years and fell into disrepair. In 2016 it was sold for about $175,000 AUD, with plans to invest further to restore it as a bed & breakfast while preserving its heritage façade, period features, and the iron-lace balcony. By the 2020s, the restoration was well underway. The owners, Ralph & Renate Wildenauer, have been working to bring it back to life, retaining historic features like the original bar area, antique elements, and period decoration, while upgrading rooms and facilities to modern standards. It now operates principally as a bed & breakfast with quietly furnished rooms that retain historic charm (period details, heritage décor) alongside modern amenities.

Orr street is the main commercial street in Queenstown. The town is pretty quiet with a population 1,772 people as of the 2021 Australian census.

The Empire Hotel in Queenstown, located right there on Orr Street, is often called the "grand old lady of the West Coast" and is a true Tasmanian icon with a rich history. It was built in 1901 during Queenstown's peak mining boom, reflecting the wealth and optimism of the era. At the time, Queenstown had many hotels, but the Empire was deliberately built taller and grander than its competitors. It has been in continuous operation for over a century, serving as a social and dining hub for the mining community and visitors.

Its prominent two-story facade is a major feature of the town's streetscape, and the hotel remains a landmark today. It stands across from where the historic Queenstown railway station was located.

Further down on Driffield street, near the corner of Orr Street, which is a central location in the town, is located the Queenstown War Memorial. It is a significant landmark that commemorates the sacrifices made by the community from the Lyell District. The memorial was originally erected to honor the soldiers of the Lyell District who fell during the Great War (World War I) 1914–1919. Over time, the memorial has been updated to include the names and commemorate service in later conflicts, including: World War II (1939–1945), The Korean War, The Vietnam War (1964–1973), and a general acknowledgment of all Australian Armed Forces.

|

|

The statue on top of the steep monument is a bronze

sculpture of an Australian infantryman

from the First World War.

Queenstown Railway Station view from Driffield street. Originally built in 1896 by the Mount Lyell Mining & Railway Company to transport copper from Queenstown to the port of Strahan. By 1963 due to increasing maintenance costs and the improvement of road access to the West Coast, the railway line closed, and the original Queenstown Station ceased operations. The track was largely removed and the line fell into disrepair over the following decades.

The current station and railway are the result of a massive reconstruction project led by locals to revive the heritage line as a tourist attraction. The restored line was officially reopened by the Prime Minister of Australia and the State Premier in 2003.

The entire line, including the Queenstown terminus, undergoes continual maintenance due to the age of the heritage equipment and the challenging, high-rainfall environment. Major infrastructure work has resulted in various temporary closures and phased re-openings over the years to ensure the railway's long-term future.

Abt Locomotive No. 3 was one of the five original steam engines built for the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company in the late 1890s. It is a legendary piece of machinery, famously involved in the rescue efforts during the devastating 1912 North Mount Lyell mining disaster.

The green metal piece is the original pressure vessel of a locomotive that spent over 60 years hauling copper ore and passengers through the King River Gorge. It is a powerful industrial relic, representing the actual component that powered the engine during its entire first working life.

This marks the end of our first day and we are now heading to Strahan to rest for the evening.

NEXT... Day 2 -Montezuma Falls