6 days in Tasmania, Australia- 5/11- 5/16/2024

5 day tour of Tasmania

Day 2 of 5 - Montezuma Falls-5/13/2024

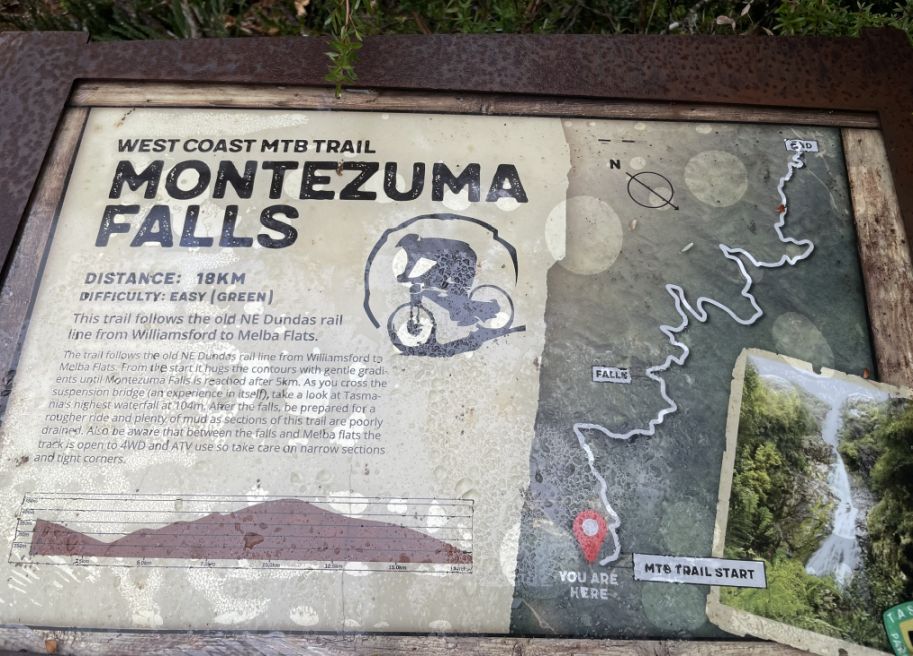

This morning Tom drove for over an hour from Strahan to reach Montezuma falls, one of Tasmania’s most spectacular natural sights, and the tallest waterfall on the island, plunging about 341 feet down a steep, forested gorge near the old mining town of Rosebery. The waterfall is located within dense temperate rainforest, filled with myrtle, sassafras, and tree ferns that thrive in the region’s cool, wet climate.

The hike to Montezuma Falls from the parking lot is about 2 miles each way, and usually takes about 2- 3 hours for a round trip at a relaxed pace.

|

|

We are now starting our hike. This walk follows a former tramway track through wet, steep, thickly forested west coast country to one of the highest falls in Tasmania. It’s amazing to ponder how they ever built a tramway here. The track eventually comes right to the base of the falls, and to a bridge that offers great views back to the falls, and out to the wild western rainforests.

As we started walking along the trail to Montezuma Falls, I noticed thick clusters of ferns spreading out beside the path. On the other side, tall, slender trees rose straight up toward the light, their trunks covered in patches of moss.

Further along the trail, we entered a section where the ferns grew incredibly tall, even much taller than us. Their broad fronds arched overhead, creating a soft green canopy. Walking beneath them felt amazing.

The trail to Montezuma Falls follows the path of the old North East Dundas Tramway, a narrow-gauge railway built in the 1890s during Tasmania’s mining boom. It once carried ore and supplies between the town of Zeehan and the remote mining settlements in the surrounding mountains.

The tramway was a remarkable feat of engineering for its time, winding through dense rainforest, crossing bridges, and cutting along steep hillsides. Today, the rails are gone, but you can still see old sleepers, rusted bolts, and remnants of the track along the way. Walking on this historic route gives a sense of what life was like for the miners and railway workers who carved their way through this rugged wilderness more than a century ago..

|

|

The track is almost entirely through pleasant and open park-like

rainforest.

How gorgeous is this scenery!

We reached Bather Creek and crossed a small wooden bridge that spanned the clear, rushing water below. The forest around us was silent except for the gentle flow of the creek until suddenly, the rain began to fall, soft at first, then steady.

As the rain picked up, we all pulled our hoodies over our heads, laughing a little as we tried to stay dry. The drizzle quickly turned into a steady shower, but it only made the forest feel more alive.

View of the bridge over the Bather Creek and from the bridge, the remnant of the old tramway looked like a section of rail still suspended on wooden posts, jutting out slightly over the creek. It was amazing to see how it had survived all these years, now covered in moss and surrounded by ferns. The sight gave a vivid glimpse into the past, as if the forest were quietly holding onto the memory of when trains once rattled through this remote wilderness.

|

|

|

Then the rain suddenly poured down heavily, within seconds, everything was soaked, but luckily I had my plastic rain gear to slip on over my clothes. The clear sheet rustled as I pulled it tight, keeping me dry while the mist and rain turned the trail into a shimmering, rain-washed path through the rainforest. But thankfully, the rain stopped as quickly as it came.

The trail is really scenic.

So far the trail is pretty flat and really easy to walk through.

Along the trail, I noticed several trees that had been uprooted and fallen across the path. Some were massive, their trunks stretching high above the ground, creating natural arches over the trail. We could easily walk beneath them, surrounded by hanging roots and moss-covered bark. It felt like part of the adventure, weaving through a forest that was constantly shifting and reshaping itself over time.

A huge fallen tree lay right across the middle of the trail, completely blocking the path, so we had to carefully hop over it to keep going. It was a fun little challenge, a reminder that this trail winds through a truly wild forest where nature still rules.

|

|

Wooden planks along the trail are actually remnants of the old railway sleepers from the North East Dundas Tramway. These sleepers once supported the metal rails that carried the small steam trams through the rainforest.

Over time, many have sunk into the ground or been covered in moss, but sections still appear along the path like a ghostly outline of the old track, reminding visitors that this peaceful walking trail was once a bustling industrial route through the wilderness.

The uprooted and fallen trees, often referred to as "windthrow" in forestry terms, are typically caused by a combination of factors, primarily severe weather and the nature of the forest and terrain. Tasmania, particularly the West Coast, is renowned for its intense and unpredictable weather systems, often featuring very strong winds, especially in the Fall and winter months when cold fronts sweep across the island.

When strong winds, sometimes reaching or exceeding 100 km/h, hit the forest, they can exert enormous pressure on the tree trunks and crowns. This can snap the trees, or, more often in wet, shallow-soil environments, it can uproot them, tearing a large plate of earth and roots out of the ground (the "root plate"). News reports frequently mention track closures due to "strong winds" bringing down "dozens of large trees" on the Montezuma Falls track specifically.

|

|

The Montezuma Falls track passes through a dense, wet, cool temperate rainforest and trees in rainforests often have relatively shallow root systems. They don't need to anchor deep into the soil to find water, and the underlying geology (like the heavy clay or rocky base of the West Coast) can limit root penetration. In a dense forest, the trees protect each other. However, when a few trees fall, it creates a gap in the canopy, exposing the remaining nearby trees to greater wind force, which can lead to a cascading effect of more trees falling (known as "domino windthrow").

The hills are full of polymetallic sulfide ores, meaning they are rich in multiple minerals such as Gold, Silver, Zinc, Lead, and Copper. The "Holes": To extract these valuable minerals, miners drove countless adits, shafts, tunnels, and cuttings into the mountainsides. These are the "holes" the sign is referring to. The hills are literally honeycombed with old mine workings.

This cave is likely one of the many abandoned mine adits or an exploratory tunnel that was dug along the route of the old tramway. The water in the creeks along the path is still often warned against drinking due to contamination (heavy metals) from this past mining activity

|

|

The panel saying "hills full of holes" points directly to the history of mining in the heart of the Montezuma Falls area. This cave is an old mine adit (a horizontal entrance to a mine). The entire West Coast of Tasmania, including the area around Montezuma Falls, Rosebery, Zeehan, and Queenstown, is part of one of the richest mineral belts in Australia, known as the Mount Read Volcanics.

In the late 19th and very early 20th century, when the Rosebery and Hercules mines (which the Montezuma Falls area is associated with) were first being prospected, the initial tunnels and shallower adits were largely created using hand tools, picks, shovels, and hammers were used to chip away at the rock and loosen the ore. This mine is really small and narrow so the work was likely done entirely by manual drilling.

|

|

Inside Tom pointed out a giant Tasmanian Cave Spider, they are very common in the dark, cool, and moist environment of old mine adits, caves, and tunnels across Tasmania. Despite their intimidating size, the Tasmanian Cave Spider is not considered aggressive or harmful to humans. They are generally shy and will retreat into a crevice if disturbed.

.I came across a panel titled “One of the Most Picturesque Sights in Western Tasmania,” and it couldn’t have described the place better. Standing there surrounded by dense rainforest, ferns, and mossy trees, it was easy to see why, the mix of natural beauty, history, and the soft sound of the nearby creek made the scene feel timeless. It was a perfect reminder of how special and untouched this part of Tasmania truly is.

We are now really close to the Montezuma falls as I hear the water cascading down.

|

|

A wooden bench next to the walking path for people to rest, or to sit and contemplate the dense, mossy cold temperate rainforest.

We are now at the most exciting part of the walk. The metal stairs leading to the suspension bridge.

We can now see part of the suspension bridge from below.

Climbing to stairs to get to the suspension bridge that crosses the Ring River/Montezuma Creek gorge.

|

|

The suspension bridge is very narrow and is essentially a one person wide path. The narrowness makes you focus entirely on your footing, placing one boot precisely in front of the other, and because it's a swing bridge, it is swaying as you walk on it. This wobble adds to the excitement, making the relatively easy walk feel like a true jungle adventure.

You'll hear the creak of the metal cables, the shifting of the planks under your feet, and the roar of the falls and the creek below echoing up from the deep gorge. It's a very acoustic experience.

As you move out over the center of the bridge you get a fantastic, lateral view of Montezuma Falls. You can see the entire massive cascade, all 341 ft. of it, tumbling down the rock tiers.

The falls were named after the Montezuma Silver Mining Company, which held leases and operated in the area in the 1890s.

The mining

company itself took its name from Moctezuma II (or Montezuma),

who was the last Aztec emperor of Mexico.

Essentially, a 19th-century silver

mining company in Tasmania named itself after a famous 16th-century Aztec

emperor, and the waterfall in the vicinity was then named after the company.

|

|

From the middle of that narrow, slightly swaying bridge, the view of the water cascading down is spectacular. You can see that it's not a single, sheer drop, but a magnificent multi-tiered spectacle. The water hits several ledges or "steps" in the steep cliff face as it makes its way down the full 341 ft.

Once you cross the bridge or follow the final stretch of the trail, you arrive at the at a viewing platform.

|

|

From this viewpoint, we are now looking directly up at the full, incredible 341 ft. height of the cascade. This view emphasizes the sheer scale of the rock face and the long, uninterrupted ribbon of falling water, making the forest canopy look tiny in comparison. It is the best spot to appreciate why it is considered one of Tasmania's highest waterfalls.

From this higher viewpoint, the suspension bridge which felt so long and wobbly when we were on it, is now framed by the dense, green rainforest. It looks like a thin, man-made thread woven through the massive natural landscape.

|

|

On the left you can see the placement of the bridge, and in the middle of the bridge is the best view of the Montezuma fall.

We are now retracing our steps back to the parking lot.

|

|

The area is managed by the Parks & Wildlife Service Tasmania and also by Sustainable Timber Tasmania (formerly Forestry Tasmania), as it often falls within state forest or reserved land rather than a formal National Park.

Since the Montezuma Falls track is designated as one of Tasmania's "60 Great Short Walks" and is a popular tourist attraction, the managing authorities have a duty to keep the path safe and accessible. If a tree completely blocks the old tramway track, it will be cut up and removed to the side of the trail.

|

|

The path winds through a very wet,

dense, and wild section of cool temperate rainforest.

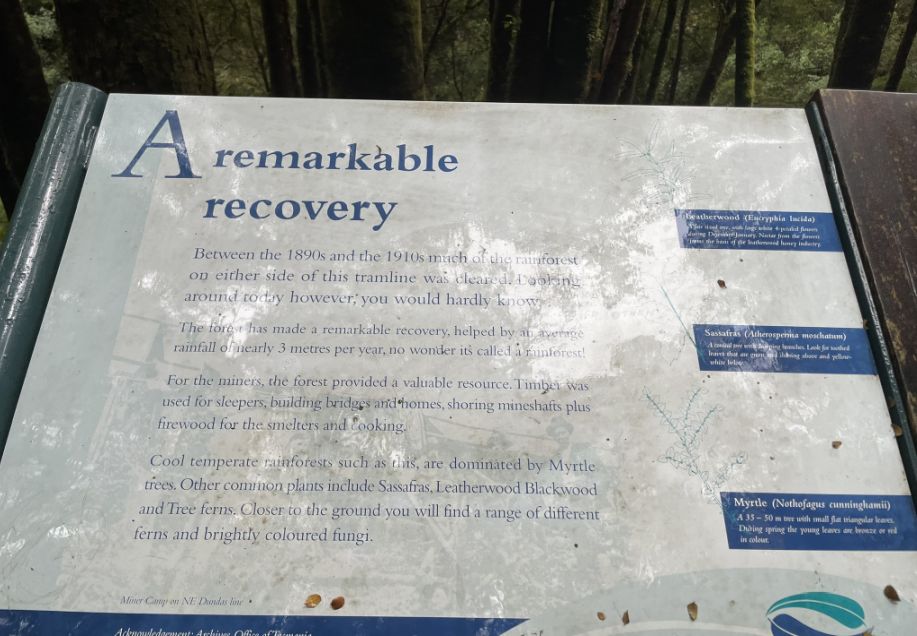

The panel talking about a "remarkable recovery" is referring to the regrowth of the temperate rainforest after a period of intense human activity. The forest on both sides of the tramway was extensively cleared to provide timber for construction (rail sleepers, trestle bridges, buildings) and fuel to stoke the steam engine furnaces and the smelters in the mining towns, In short, the area was heavily exploited and disturbed.

Today we are walking through is essentially a second-generation rainforest, a relatively young forest that has returned since the tramway was abandoned and the human activity ceased. The incredible speed with which the temperate rainforest has reclaimed the land. In the century since the tramway was abandoned, the forest has grown back so thickly that it's difficult to imagine it was once a clear-felled industrial corridor. The recovery shows the resilience of nature. Even after severe logging and industrial activity, the high rainfall, fertile soil, and protected status of the area have allowed the forest to regenerate into the beautiful, "park-like" and thick rainforest you see today.

Crossing the last bridge before heading to the parking lot.

|

|

This is the end of our walk.

Map of the Montezuma trail.

NEXT... Henty Dunes and Ocean Beach