Sydney, Australia-12/26/2017 -1/1/2018

Day 6-Hyde Park Barracks Museum-12/31/2017

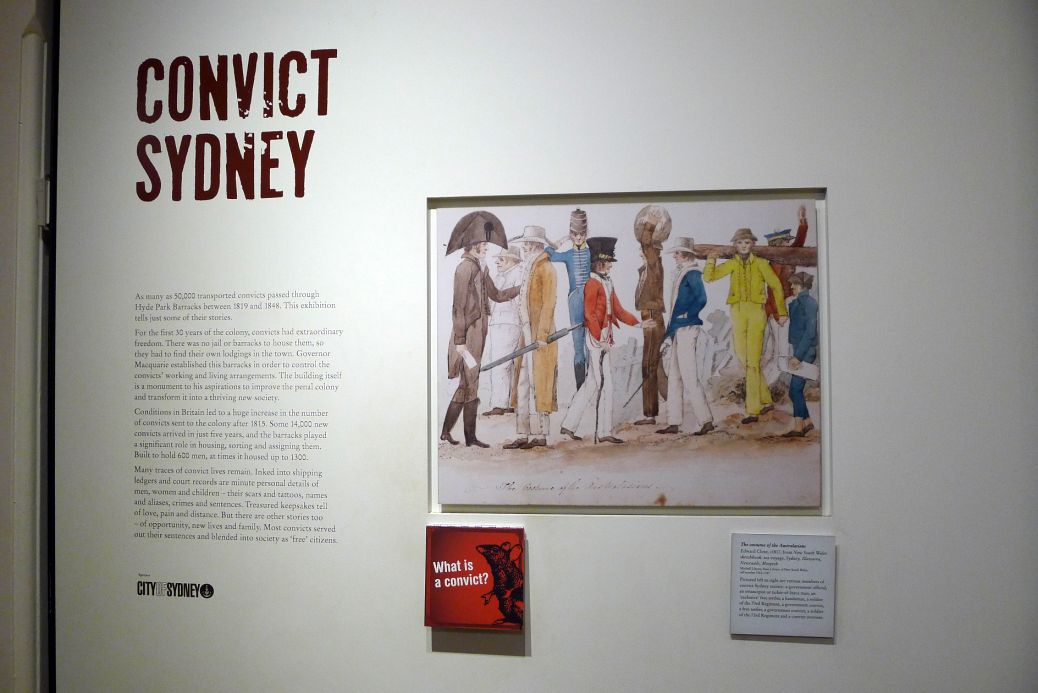

The World Heritage listed Hyde Park Barracks as one of the most significant convict site in the world. The museum charts the history of the barracks (opened in 1819), which served as inmate housing in the world’s largest and longest-running convict transport system, an immigration depot for 2,253 Irish orphan girls fleeing the Great Famine, an asylum for elderly women, and eventually, courts and government offices

The site is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as one of 11 pre-eminent Australian Convict Sites as amongst "the best surviving examples of large-scale convict transportation and the colonial expansion of European powers through the presence and labor of convicts", and was listed on the Australian National Heritage List on 1 August 2007.

We passed by Hyde Park Barracks located on Macquarie street a few days ago and now we are getting inside to see the museum.

It was not until 1975 that extensive conservation works began, and the main building was restored to its original appearance. When workers began to discover relics from the convict period in the cracks and corners of the building, archaeologists were called in to investigate. About 100,000 personal and sometimes precious fragments were then recovered from beneath the floorboards – items which had been left behind or stashed for safekeeping by convicts, women and court workers.

The convicts who stayed at the Barracks were selected to work for the government because they had special skills, trades or professions, and could provide the government with all the skills necessary to build the colony. There were bakers, brick makers, boat builders, shoemakers, stonemasons, blacksmiths, weavers, carpenters, miners, potters and clerks, and just about any other trade you can name. Three quarters of the English convicts could read, or read and write, and the Irish convicts were on average less educated, but all convicts tended to better educated than the general working population in England.

|

|

Visual displays of artifacts, such as convict carpentry tools, are mixed with audio installations and interactive experiences.

Typewriter for typist to record office affairs for clerks to bind in red tape. |

Fork, spoon, knife, plate used by convicts. |

Much of this material had been pulled under the floorboards by the rats that infested the building through most of its history, scurrying, stealing and collecting rubbish to make their nests.

|

|

|

This collection, which reveals so much about how these men and women lived, still comprises one of the most significant archaeological collections in Australia, and is a unique archive of 19th-century textiles and institutional life.

Objects that belongs to a seamstress.

|

|

|

Hats that was worn by Irish orphan girls or elderly women that used to live here.

A trunk belonging to a female immigrant. Probably everything they own are in this trunk.

In 1848, the barracks was transformed to house Sydney’s female Immigration Depot, much needed due to the increasing numbers of free immigrants arriving in the colony.

For 38 years it provided temporary shelter and a safe haven for an estimated 40,000 immigrant women, some accompanied by their children. By day the women waited to be collected by friends or family, or to be employed from the hiring room on the ground floor. At night they slept on simple iron beds in dormitories. They all made the difficult decision to leave their homelands and take their chance for a new life in a land of opportunity.

|

|

|

One of the original wall.

|

|

|

Original floor that was built by the convicts and doorway in deputy superintendent's office,

While original doorways, limewashed bricks, floorboards, roof timbers, paint and plaster show the original character and layers of adaptation in each space.

Fireplaces - Read description below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The ghost stair is am abstract line tracing the handrail of the original stair. It links three approaches to building conservation & historical interpretation: Level 1 modern adaptation for exhibition, level 2 exposed layers of historical use, level 3 theatrical reconstruction of convict past. All conservation processes use evidence to uncover the past in different ways.

|

|

Convict carpentry and building tools on display.

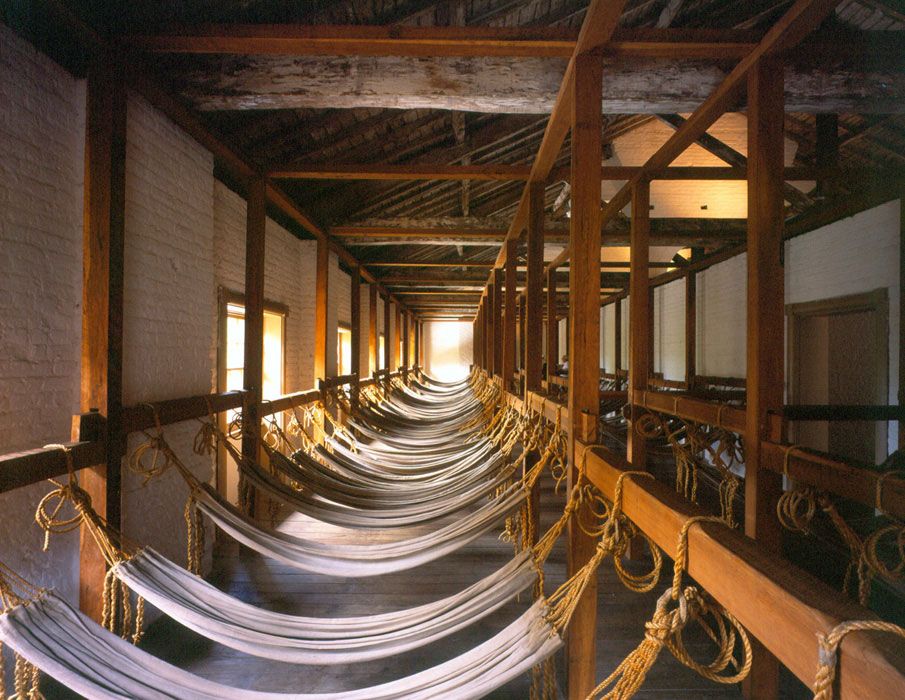

Large painting of the wall.

About 80,000 convicts were sent to New South Wales between 1788 and 1849, and estimate that after Hyde Park Barracks was opened in 1819, at least 50,000 of these convicts passed through its gates. After being landed from the transport ships arriving in Sydney Cove, many convicts were marched up through the Governor’s Domain and mustered in the Barracks yard before being assigned to work for private employers, or held at the Barracks if they had skills the colonial government needed. Barracks convicts slept in the dormitories strung up with hammocks, and went out each day to work in gangs on government roads, docks, quarries or building projects. Other convict men and women came from around the colony to stand trial at the Barracks Bench, or Court of General Sessions. The unlucky ones also suffered brutal punishment in solitary confinement and on the flogging triangle behind the eastern compound wall.

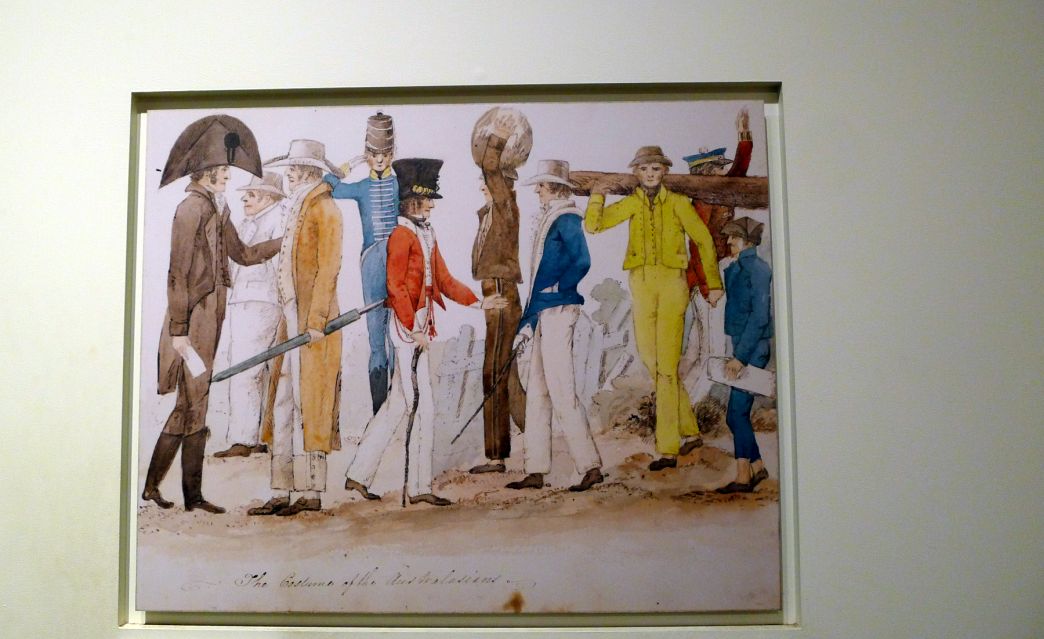

The costume of the Australian by Edward Close, Circa 1817

Picture left to right are various member of convict Sydney society: a government official, an emancipist or ticket-of-leave man, an "exclusive" free settler, a government convict, a free settler, a government convict, a officer of the 73rd regiment and a convict overseer.

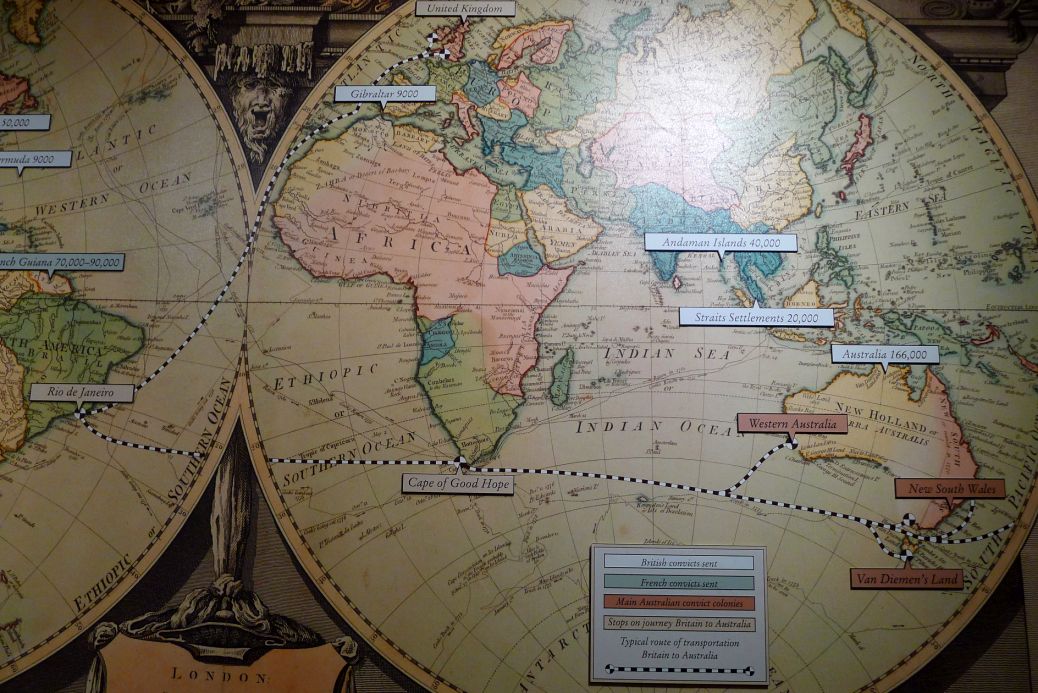

The convicts were a motley crew, hailing from all parts of Britain and her colonies around the world. Of those convicts sent to NSW, about 60 per cent were English, 30 per cent Irish, and the other 10 per cent were Scottish, Welsh and from other parts of the British Empire. There are also some convicts who came from places as exotic as South Africa, Jamaica, Canada, Portugal and Prince of Wales Island (now Malaysia).

|

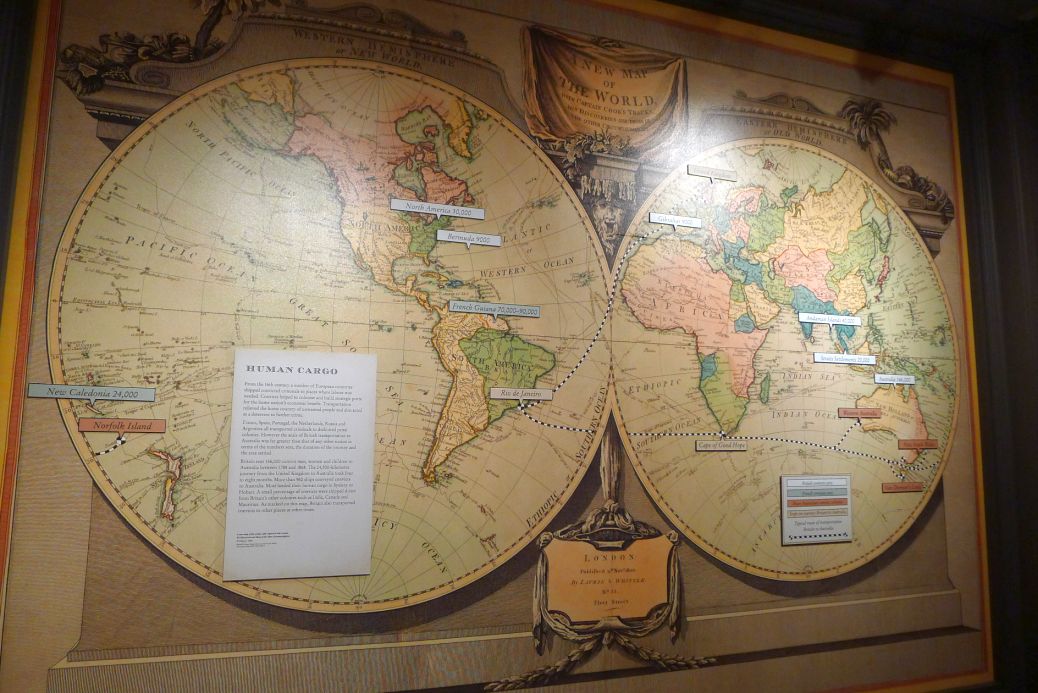

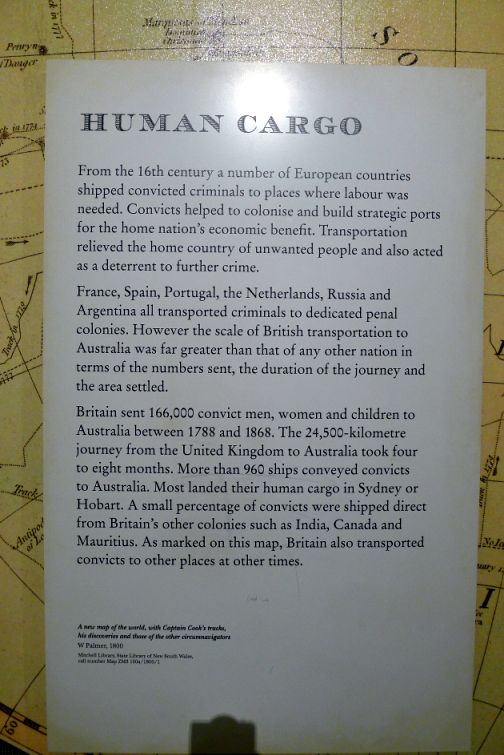

Map of where the convicts were sent.

Barracks convicts slept in the dormitories strung up with hammocks, and went out each day to work in gangs on government roads, docks, quarries or building projects. Other convict men and women came from around the colony to stand trial at the Barracks Bench, or Court of General Sessions. The unlucky ones also suffered brutal punishment in solitary confinement and on the flogging triangle behind the eastern compound wall.

Dormitories filled with hammocks, soundscapes and the chiming clock take you back to the time when the building was crammed full with convicts.

|

|

Not very comfortable to sleep in for sure!

The records are full of names of individuals who committed repeat offences, who were thrown into solitary confinement, sentenced to walk on the treadmill, or to be flogged on the triangle outside the Barracks wall. Some even became notorious escapees, gamblers, swindlers, bushrangers and murderers. These convicts were banished from Hyde Park Barracks to more brutal places of secondary punishment, where they suffered the full range of severe punishments that the colonial government had to offer, some spending the rest of their lives in prison.

In the colony, their lives unfolded for better or for worse. Most convicts were well-behaved and soon gained their freedom through hard work and obedience, but some convicts just couldn’t stay out of trouble.

This is what might look like when the convicts used to live here.

NEXT... Day6- Queen Victoria building/Lunch